Beyond Li and Wang: The Hidden World of Chinese Compound Surnames (复姓)

Most Chinese surnames are a single character, but a small group of multi-character ‘compound surnames’ preserve traces of ancient titles, clans, and borderland tribes. This guide explains what 复姓 are, where they came from, and what they signal in modern Chinese.

If you’ve spent any time around Chinese names, you probably recognise the big single-character surnames:

李 Lǐ, 王 Wáng, 张 Zhāng, 刘 Liú, 陈 Chén…

These “one-character surnames” (单姓 dānxìng) dominate modern China. The top 100 surnames—almost all of them single-character—cover around 85–86% of the population.

But every now and then you meet someone whose surname is two full characters:

欧阳 Ōuyáng 上官 Shàngguān 司马 Sīmǎ 诸葛 Zhūgě

These are compound surnames, or 复姓 fùxìng / 複姓: multi-character Chinese surnames that function as a single family name. They’re rare today, but they carry a surprising amount of history.

This article is a deep dive into that world:

- what exactly counts as a 复姓

- how common (or uncommon) they really are

- where they came from: titles, places, clans, and non-Han peoples

- how compound surnames behave in modern life and paperwork

- whether a learner should ever choose one as their own surname

- and how to recognise them when you see them

What is a compound surname (复姓)?

In Chinese, 复姓 / 複姓 literally means “compound surname”. Formally:

A 复姓 is a Chinese surname made of two or more characters, which functions as a single inherited family name.

Examples:

- 欧阳 Ōuyáng

- 上官 Shàngguān

- 司马 Sīmǎ

- 诸葛 Zhūgě

- 皇甫 Huángfǔ

- 夏侯 Xiàhóu

- 令狐 Línghú

These contrast with 单姓 (single-character surnames) such as 李 Lǐ or 王 Wáng.

A couple of important clarifications:

- A 复姓 is not the same as a modern “double surname” that simply puts father’s + mother’s surnames together (often called 双姓). 复姓 are old, fixed surnames with their own origin stories, not ad-hoc combos.

- Many 复姓 are two characters, but there are also rarer three- or four-character surnames, especially from non-Han lineages (e.g. 爱新觉罗 Àixīnjuéluó, the sinicised form of the Manchu Aisin Gioro clan).

Think of 复姓 as:

“A family name that just happens to need two (or more) syllables to say.”

How common are compound surnames?

Short answer: not very.

1 Overall surname landscape

Modern studies suggest:

- Only a few thousand surnames are in active use across China, with roughly 3,000 among the Han majority.

- The top 100 surnames—almost all single-character—cover about 85–86% of the population.

Compound surnames are a tiny minority of that total.

2 How many compound surnames exist?

Classical sources such as the Hundred Family Surnames (《百家姓》) include around 60 compound surnames.

Modern scholars and surname catalogues list dozens more, especially when including:

- historically attested but now-extinct 复姓

- non-Han surnames recorded in Chinese characters

The Chinese Wikipedia article on 複姓, for example, gives an alphabetised list of over 200 multi-character surnames, including many that are now extremely rare.

3 Which compound surnames are actually common today?

Among all compound surnames, only a handful are found with any frequency in modern Mainland China:

欧阳 Ōuyáng, 令狐 Línghú, 皇甫 Huángfǔ, 上官 Shàngguān, 司徒 Sītú, 诸葛 Zhūgě, 司马 Sīmǎ, 宇文 Yǔwén, 呼延 Hūyán, 端木 Duānmù…

A 2020 report from China’s Ministry of Public Security notes that:

- 欧阳 Ōuyáng is the most common 复姓 on the mainland, with about 1.11 million bearers (still less than 0.1% of the population).

- Other compound surnames have populations in the tens or hundreds of thousands at most.

In Taiwan, the top five compound surnames by population are: 欧阳, 司徒, 上官, 端木, 诸葛.

So if you meet someone called 欧阳 X, that’s not shocking. But overall, 复姓 are rare enough to feel special.

Where did compound surnames come from?

One reason compound surnames fascinate people is that each one is basically a mini history puzzle. They don’t share a single origin; instead, they fall into several big families of stories.

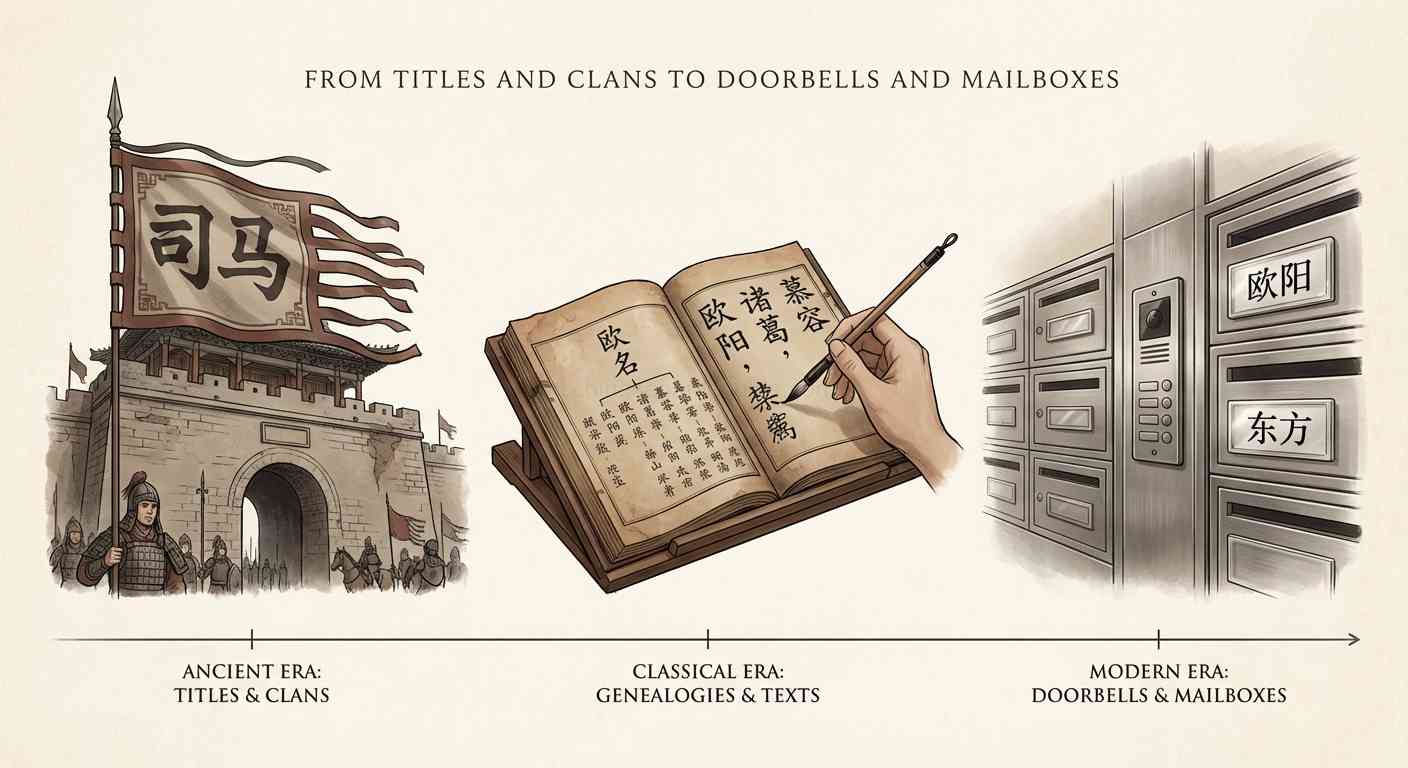

1 Noble titles and high offices

Many 复姓 began life as official titles or noble ranks, especially around the Zhou and Han dynasties.

Some classic examples:

- 司马 Sīmǎ – literally “controller of horses”, originally an important military/administrative office. Later also used as a noble title; the Sima clan eventually founded the Jin dynasty.

- 司徒 Sītú – title sometimes translated as “Minister over the Masses”, one of the top three imperial offices in some periods.

- 司空 Sīkōng, 太史 Tàishǐ, 乐正 Yuèzhèng – titles for the Minister of Works, Grand Historian, and Minister of Music. These also became hereditary surnames.

In these cases, the family is literally named after “Grand Historian”, “Minister of Works”, etc.—you can read the bureaucratic hierarchy in their surname.

2 Place names and “gate addresses”

Another big group comes from places: city gates, regions, or fiefdoms.

- 东方 Dōngfāng, 南宫 Nángōng, 东门 Dōngmén, 西门 Xīmén, 东郭 Dōngguō, 濮阳 Púyáng, etc.

These often started as descriptions like:

“The family that lives by the East Gate” → 东门 “The clan from the southern palace complex” → 南宫

Over time, that description froze into a hereditary surname.

3 Personal names, courtesy names, posthumous titles

Some compound surnames trace back to the given name / courtesy name / posthumous title of a prestigious ancestor.

For example, the 複姓 article mentions:

- 轩辕 Xuānyuán – the personal name of the Yellow Emperor in legend. His descendants were said to take it as a surname.

- 皇甫 Huángfǔ – originally derived from 皇父 (a noble’s courtesy name) in the state of Song.

Here the story is: “We are the descendants of so-and-so, whose given/courtesy title was X” → that title becomes the surname.

4 Non-Han clans becoming Chinese surnames

Many 复姓 entered Chinese as sinicised names of non-Han peoples, especially during periods of frontier expansion and conquest.

Examples include:

- 慕容 Mùróng, 宇文 Yǔwén, 赫连 Hèlián, 拓跋 Tuòbá – associated with Xianbei and other northern steppe groups.

- 阿史那 Āshǐnà – reflecting a Turkic clan name (often linked to “Asena” wolf myth).

- Multi-character surnames like 爱新觉罗 Àixīnjuéluó (Aisin Gioro), the ruling clan of the Qing dynasty.

These names froze complex foreign sounds into Chinese characters, then persisted as hereditary surnames even after deep cultural integration.

5 Hybrids, merges, and later simplification

There are also compound surnames formed by:

- joining two single-character surnames

- combining a place name + clan name

- adding a generation marker to an original surname, and so on.

Over centuries, many 复姓 collapsed into single-character surnames for convenience:

- some branches of 司马 became 马 Mǎ

- some descendants of 诸葛 became 葛 Gé

- others adopted different single-character “cover surnames” during migrations or to avoid political trouble

That’s why today’s list of active compound surnames is much shorter than the sprawling lists preserved in historical texts.

复姓 vs “double-barrelled surnames” in the West

If you come from an English or Spanish background, compound surnames might remind you of:

- “double-barrelled” surnames like Smith-Jones,

- Spanish-style father + mother surnames (García Márquez, etc.).

Superficially these look similar, but in Chinese the logic is different.

- A 复姓 is a single family name that happens to have more than one character and has usually existed for centuries. You can’t “split” 欧阳 into 欧 + 阳 as two separate surnames; they’re just one unit.

- Modern “double surnames” created by combining parents’ surnames—like 王李 or 陈张—are not 复姓 in the classical sense. They’re newer experiments, sometimes called 双姓, with different legal and cultural status.

So if you see 欧阳娜娜:

- 欧阳 is one surname

- 娜娜 is the given name

It’s not “Ms Ou and Ms Yang”; it’s “Ms Ouyang Nana”.

How compound surnames behave in modern life

Because 复姓 are structurally different, they create some very practical quirks in daily life and bureaucracy.

1 Name length and rhythm

With a compound surname, the full Chinese name usually has:

- 2-character surname + 1-character given name → 3 characters total

- 欧阳修 Ōuyáng Xiū (Song dynasty writer)

- 司马光 Sīmǎ Guāng (historian)

or

- 2-character surname + 2-character given name → 4 characters total

- 欧阳明义 Ōuyáng Míngyì (hypothetical)

- 上官婉儿 Shàngguān Wǎn’ér (historical Tang figure)

To native ears, both patterns are fine; 3- and 4-character full names are common.

2 Forms, databases, and “where do I cut this thing?”

Many computer systems—especially older ones—are designed with the assumption:

“Surname = 1 character, given name = the rest.”

This breaks if your surname is 欧阳, 司马, or 诸葛.

Common issues:

- Systems automatically treat 欧 as surname and 阳 as given-name character.

- Officials unfamiliar with 复姓 may enter names incorrectly on forms.

- When sorting alphabetically in Pinyin, some systems mistakenly split the surname.

People with compound surnames often need to manually correct or annotate:

- “My surname is Ouyang, not Ou.”

- “Please put both characters in the surname field.”

In international passports and visas, you’ll also see variation:

- “OUYANG Nana”,

- “OU YANG Nana”,

- occasionally “Ouyang Nana” with space after the full Chinese name.

None of this changes the fact that 欧阳 is one surname, but it does create small annoyances.

3 Romanisation: one word or two?

In Hanyu Pinyin, the surname is usually written as one word:

- Ouyang, Shangguan, Sima, Zhuge, Situ, Huangfu, Murong, Nangong, etc.

However, you’ll also see variations:

- OU-YANG, OU YANG, SHANG-GUAN, etc., especially in older passports or overseas communities.

If you adopt or work with a compound surname in English, it’s worth picking a stable spelling and sticking to it across documents.

What does having a compound surname feel like?

Because 复姓 are rare and historically loaded, they carry a distinct vibe.

1 “Elegant”, “aristocratic”, sometimes “dramatic”

Many famous 复姓 are tied to:

- historical elites (诸葛亮 Zhuge Liang, Sima Qian, the Sima Jin emperors),

- legendary clans (Murong, Tuoba),

- or aristocratic families in novels and dramas.

So to many native speakers, names like:

- 欧阳, 上官, 司马, 诸葛, 慕容

sound slightly literary, aristocratic, or wuxia-coded.

That can be fun—but if a foreign learner suddenly calls themselves “Zhuge [something]”, it may feel like you stepped straight out of a Three Kingdoms fanfic.

2 A built-in conversation starter

Because they’re unusual, compound surnames almost guarantee small talk:

“哦,你是欧阳?你们家族是哪一支的?” “Wow, you’re an Ouyang? Which branch is your family from?”

or

“诸葛?那你和诸葛亮有关系吗?” “Zhuge? Any relation to Zhuge Liang?”

If you actually come from such a family, that’s normal. If you picked the name yourself, be prepared to explain why.

Should a learner ever choose a 复姓?

You can, but it’s a high-impact choice. Let’s break down pros and cons.

1 Potential upsides

-

Distinctiveness You will almost never collide with other foreigners’ Chinese names, and even among Chinese people, your surname will stand out.

-

Memorability & “story hook” People remember “Ouyang [Name]” better than yet another “Li [Name]”. You also get a built-in excuse to talk about Chinese surname culture.

-

Cultural depth (if you do your homework) If you have a genuine connection—e.g. a teacher with that surname adopts you as a formal student, or you’re working intensively on a particular historical period—adopting a 复姓 can be meaningful.

2 Real downsides

-

Bureaucratic friction You’ll be fighting the “surname = 1 character” assumption in online forms, student systems, conference badges, etc.

-

Risk of sounding overly theatrical Picking something like 诸葛 or 慕容 with no context can feel like choosing “van Skywalker” as a surname in English. It’s not wrong, but it’s loud.

-

Steeper learning curve Because 复姓 are rare, you need to understand them better to avoid strange combinations. A beginner wearing “Shangguan Dragon God” as a name will make native speakers wince.

3 Safer guidelines if you really want a compound surname

If you decide to go for it anyway:

- Favour relatively common, low-drama 复姓 like 欧阳, 上官, 司徒, 端木, rather than extremely legendary ones.

- Pair it with a simple, tasteful given name (1–2 characters) that sounds like a real modern name, not a fantasy novel title.

- Be ready to explain your choice humbly:

- “My teacher is Ouyang, they helped me choose this as a symbolic surname.”

- “I study texts about the Sima clan; my teacher suggested this name.”

If you just want a good, natural Chinese name, a one-character surname (李, 王, 陈, 林…) is much easier and more typical.

How to spot a compound surname in the wild

When you see a 3–4 character Chinese full name, you can sometimes guess whether the surname is compound.

Tips:

-

Check the first two characters against known 复姓 lists. Common modern ones include: 欧阳, 上官, 司马, 诸葛, 皇甫, 司徒, 夏侯, 慕容, 令狐, 宇文, 端木, 呼延, 南宫, etc.

-

Look at tone and structure. In many cases, the two characters of the surname form a meaningful phrase:

- 上官 = “high official”

- 东门 / 西门 = “east gate / west gate”

- 皇甫 (originally from a noble title)

-

Database telltales. If you see inconsistent splits in different places—e.g. sometimes 欧阳娜娜 is mis-indexed as 欧 娜娜—that’s a hint the system doesn’t recognise the 复姓.

With a bit of exposure, your brain will start flagging the common compound surnames automatically.

Takeaways: 复姓 as living fossils of Chinese history

Compound surnames are not a central part of daily name usage—the vast majority of Chinese people have single-character surnames, and most learners should probably pick one of those too.

But 复姓 are like living fossils embedded in the naming system:

- Some preserve traces of ancient bureaucratic offices (“Grand Historian”, “Minister of Works”).

- Others carry the memory of city gates, fiefdoms, and legendary ancestors.

- Many mark the deep integration of non-Han clans into the Chinese world.

If you’re serious about Chinese names, understanding 复姓 will:

- make historical texts and novels much clearer,

- help you parse long names and know where the surname ends,

- and give you a richer sense of how identity, geography, and bureaucracy all got baked into the Chinese surname system.

You don’t have to wear a compound surname to appreciate them. But once you see how they work, every 欧阳, 司马, or 诸葛 you encounter will read as a tiny story about how that family entered the vast web of Chinese history—and chose to keep that story alive in two characters instead of one.

Related Articles

What Counts as a *Classic* Chinese Name? From Confucius to Grandma Zhang

When people say “classic Chinese names”, they might picture Confucius, Li Bai… or Auntie Wang downstairs. This guide unpacks what ‘classic’ really means, how traditional names were built, and how to create a name with an old-school Chinese feel today.

When Your Name Sounds Wrong: Tone, Rhythm, and Ping-Ze in Chinese Names

Meaning isn’t everything. This guide shows how tones, rhythm, and classical ping–ze patterns quietly shape what counts as a ‘good-sounding’ Chinese name—and how non-native speakers can avoid clunky, tongue-twister names.