Why Two-Character Chinese Names Dominate (And What They Actually Do)

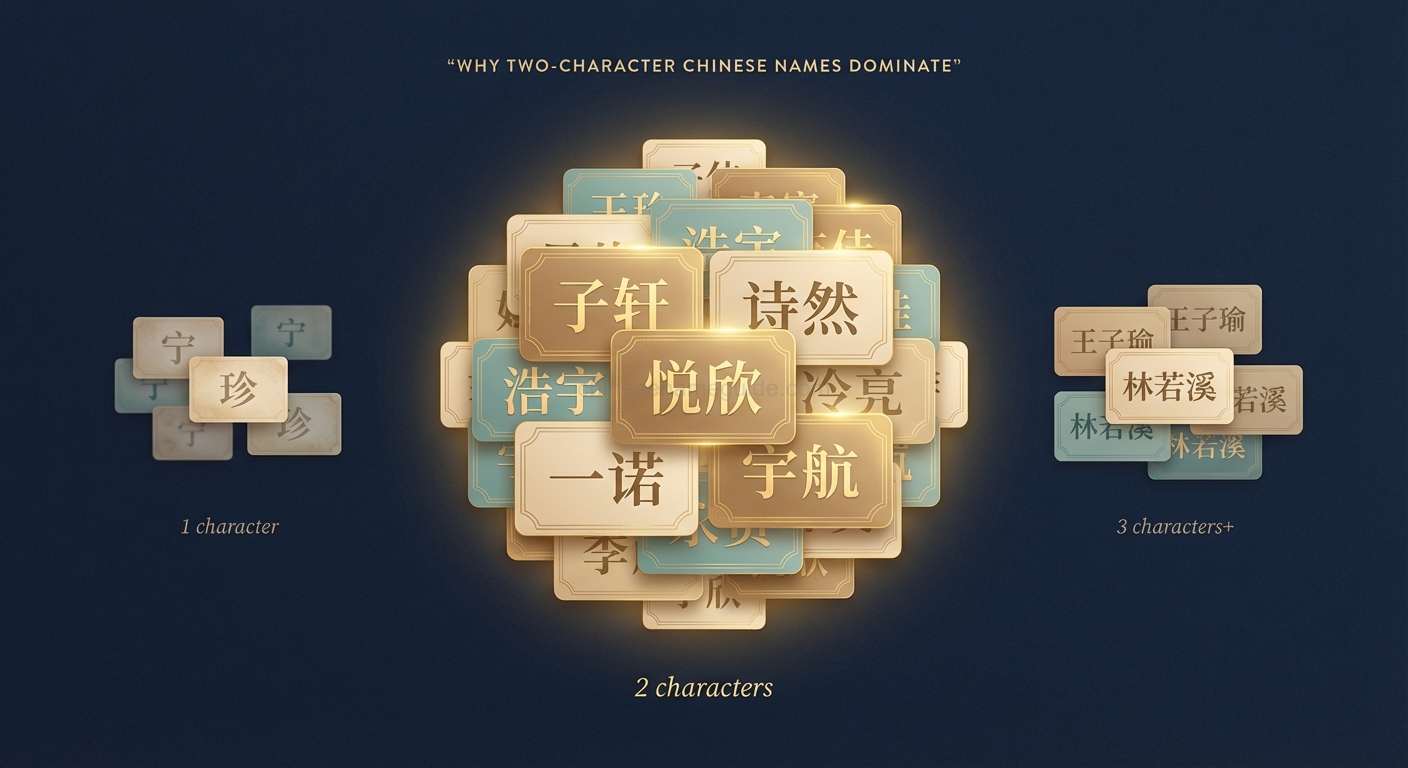

Most modern Chinese given names have exactly two characters. This article explains why that pattern dominates, how it evolved, and how two-character names encode gender, family, and personality.

Open almost any list of modern Chinese baby names and you’ll see the same basic shape over and over:

李宸宇 Lǐ Chényǔ 王佳宁 Wáng Jiāníng 陈子涵 Chén Zǐhán

One-character surname + two-character given name.

This isn’t a coincidence or a temporary fashion. Studies have repeatedly found that in contemporary Mainland China, the large majority of Han Chinese given names are two characters long—often 80–90% of newborns in recent decades.

So if you want to understand Chinese names at all—especially if you’re choosing one for yourself—you need to understand two-character given names.

This article focuses on that pattern:

- what “two-character Chinese name” usually means

- how it became dominant (it wasn’t always)

- what two characters allow you to express that one cannot

- the most common structural patterns

- and some do’s and don’ts if you’re designing a two-character Chinese name as a learner.

First, a quick structural reset: surname + given name

In modern Chinese, a full personal name is normally:

[Surname 姓] + [Given name 名]

- The surname is almost always one character: Li 李, Wang 王, Zhang 张, Chen 陈, etc.

- The given name is one or two characters.

- So most people have full names with two or three characters total.

When people talk informally about “two-character names”, they often mean:

- either “two-character given names” (what this article focuses on),

- or “two-character full names” (one-character surname + one-character given name).

In practice, two-character full names are a minority: most Han Chinese nowadays have one-character surnames and two-character given names, yielding three-character full names.

So when you see “two-character Chinese names” in name lists or guides, it almost always means two-character given names like:

- 子涵 Zǐhán

- 智勇 Zhìyǒng

- 佳怡 Jiāyí

How did two-character given names become the default?

Historically, Chinese given names weren’t always dominated by two characters.

1 Early empire: mostly one-character given names

In early periods (like the Han dynasty), most given names were single characters, and two-character given names were rare. At one point, the usurper Wang Mang even banned two-character given names, pushing the proportion of one-character names above 98%.

2 Tang/Song to Ming/Qing: two-character names gain ground

Over time, especially by the Tang and Song dynasties, two-character given names became more common and eventually the majority in some periods. Later, under the Ming and Qing dynasties, the “surname + two-character given name” pattern became more established, helped by:

- large clans using generation names (one fixed character shared by all siblings/cousins of a generation, plus one free character),

- a desire to express more nuance and individuality as populations grew.

3 20th century swings and modern dominance

Data from the 20th century show some swings:

- In the mid-20th century, two-character given names were the clear majority.

- From the 1950s–1980s, there was a noticeable rise in one-character given names in some cohorts, influenced by political trends, simplification, and fashion.

- From the 1990s onward, two-character given names recovered and again became dominant, reaching around 90% for male names and 80% for female names in some datasets by the early 2000s.

Short version:

Today, if you meet a Mainland Chinese person born in the last few decades, odds are high their given name has two characters.

Why two characters? The practical and cultural sweet spot

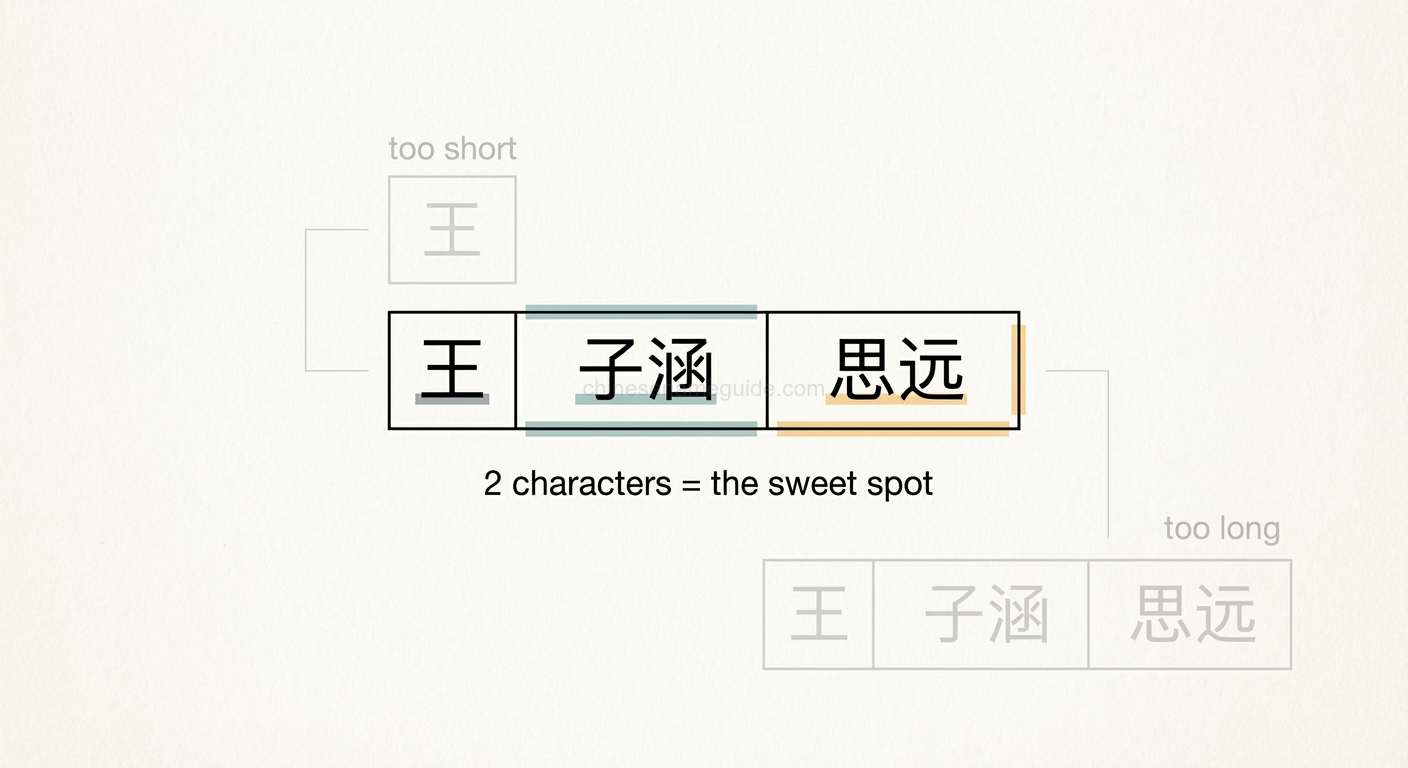

Why didn’t one-character names stay dominant? Why not three?

Chinese naming has to solve several constraints at once:

- Few surnames, many people

- A huge pool of characters, but not all are useful for names

- Cultural expectations about meaning, sound, and aesthetics

- Practical issues like typing, paperwork, and uniqueness

Two-character given names hit a sweet spot.

1 Avoiding massive duplication

China has very few common surnames: just the top three—Wang 王, Li 李, Zhang 张—already cover more than 20% of the population, and a few hundred surnames cover the vast majority of Han people.

If you also limited given names to one character, you’d get:

- Li Wei 李伟

- Wang Wei 王伟

- Zhang Wei 张伟

everywhere you look. This already happens to a degree; some names are notoriously common.

Two-character given names:

- square the number of possible combinations,

- make it easier to get a name that isn’t shared by thousands of people,

- still stay short and manageable in daily life.

2 More space for meaning

Chinese given names are almost always meaningful: each character carries semantic weight.

With two characters, you can:

-

combine virtue + talent:

- 德文 Déwén – virtue + literature

- 仁博 Rénbó – benevolence + breadth

-

combine nature + feeling:

- 雨欣 Yǔxīn – rain + joy

- 林静 Línjìng – forest + calm

-

combine family generation + individual trait (see next section)

A one-character name can be powerful and elegant, but it communicates less and gives fewer options for family traditions.

3 Good balance between simplicity and expressiveness

Three-character given names exist but are rare; they:

- feel heavy in everyday use,

- are more likely to cause issues in forms and systems,

- risk looking unusual or pretentious unless done carefully.

Two characters, on the other hand:

- are easy to remember, write, and call out

- offer enough “design space” for meaning, sound, and family patterns

- fit well with one-character surnames (most full names become three syllables, which flows nicely in Mandarin)

The classic “generation + personal” structure

One of the most important uses of the two-character given name is the generation name tradition.

In many families, particularly larger or more traditional ones, one character in the given name is:

- shared by all siblings and cousins of the same generation,

- while the other character is unique to the individual.

Example:

- Grandfather picks a two-character phrase for future descendants, e.g. “(X) (Y) … 德 (virtue) … 文 (culture) … 仁 (benevolence) … 义 (righteousness)” and so on.

- For one generation, everyone’s first given character is 德:

- 李德明 Lǐ Démíng

- 李德华 Lǐ Déhuá

- 李德军 Lǐ Déjūn

- For the next generation, everyone’s first given character is 文:

- 李文婷 Lǐ Wéntíng

- 李文博 Lǐ Wénbó

- 李文杰 Lǐ Wénjié

Here, 德 / 文 are generation characters; 明 / 华 / 军 / 婷 / 博 / 杰 are personal characters.

Two-character given names are almost perfect for this:

- one slot reserved (family tradition),

- one slot free (individuality).

You can do generation names with single-character given names (by changing the surname or borrowing from elsewhere), but structurally it’s much cleaner with two.

Common pattern types in two-character given names

Seen enough two-character names and you’ll start noticing templates. Below are some of the most common “shapes”, with example characters (not recommendations to copy blindly).

1 Virtue + virtue

These names signal values directly:

- 德文 Déwén – virtue + culture

- 志远 Zhìyuǎn – ambition + far

- 仁义 Rényì – benevolence + righteousness

Common virtue characters include 德 (virtue), 仁 (benevolence), 信 (trust), 志 (will/aspiration), 勇 (courage), 勤 (diligence), and so on.

2 Nature + quality

One character from nature, one from quality / feeling:

- 雨欣 Yǔxīn – rain + joy

- 林安 Lín’ān – forest + peace

- 岚清 Lánqīng – mountain mist + clear

Nature-side characters: 林 (forest), 山 (mountain), 雨 (rain), 星 (star), 月 (moon), 岚 (mist), 川 (river)…

Quality-side characters: 安 (peace), 宁 (calm), 清 (clear), 朗 (bright), 明 (bright), 睿 (wise)…

3 Time / cosmos + aspiration

A very popular modern cluster combines cosmic imagery with hopes for the future:

- 宇辰 Yǔchén – cosmos + celestial time

- 昊天 Hàotiān – vast sky + sky

- 晨曦 Chénxī – morning + dawn light

Here you see characters like 宇 (universe), 宙 (space-time), 昊 (vast sky), 辰 (heavenly bodies/time), and 晨 / 曦 (morning/dawn).

4 Gendered “softness” and “strength”

Two-character given names are also where many gendered patterns live, especially in older generations.

Traditional feminine-leaning patterns:

- 美 + something: 美玲 Měilíng, 美华 Měihuá

- 芳 / 娟 / 静 / 婷: 秀芳 Xiùfāng, 静怡 Jìngyí, 婷玉 Tíngyù

- flower/nature + soft quality: 莲芳 Liánfāng (lotus + fragrance), 雪琴 Xuěqín (snow + zither)

Traditional masculine-leaning patterns:

- strong adjectives: 强军 Qiángjūn (strong + army), 刚毅 Gāngyì (firm + resolute)

- aspiration characters: 建国 Jiànguó (build the nation), 伟民 Wěimín (great + people)

- natural power: 海波 Hǎibō (sea + waves), 山峰 Shānfēng (mountain peak)

Modern naming has softened this gender divide, but the echoes are still there.

5 Reduplicated names (AA pattern)

Some names repeat the same character:

- 晶晶 Jīngjing

- 佳佳 Jiājiā

- 冉冉 Rǎnrǎn

These used to be especially common in informal or affectionate names and in female names; in modern times they’re also used as legal given names, especially for girls and younger children.

What two-character names do sound-wise

Besides meaning, two-character names let you work with rhythm and tone.

A two-character given name sits after a one-character surname, so the full name is typically:

X (surname) + YZ (given)

- Three syllables total: good for chanting, calling, and remembering.

- Tone contours matter: parents may avoid awkward tone sequences (e.g. multiple third tones in a row) and aim for a pleasant pitch pattern when the full name is spoken.

Two-character given names also make it easier to avoid:

- tongue-twisters with the surname,

- unintentional homophones with common phrases or slang.

For example, if your surname is 马 Mǎ (“horse”), you might think twice about a one-character given name like 上 Shàng (“on/up”), because 马上 Mǎshàng = “immediately” is a very common phrase. But 马晨曦 Mǎ Chénxī doesn’t have that issue.

Designing a two-character Chinese given name as a learner

If you’re choosing a Chinese name for yourself, two-character given names are usually the safest and most natural choice, especially if you want to blend into modern mainland or Taiwan naming patterns.

Here’s a practical way to do it.

Step 1: Fix a reasonable surname

Pick a very common one-character surname unless you have a specific reason not to:

- 李 Lǐ, 王 Wáng, 张 Zhāng, 刘 Liú, 陈 Chén, 林 Lín, 周 Zhōu, 赵 Zhào, etc.

Using rare or compound surnames (like 欧阳 Ōuyáng) can be interesting, but adds complexity you probably don’t need.

Step 2: Decide your “tone”: classic, modern, or neutral

Ask yourself:

- Do I want to sound pretty timeless, like a teacher or academic might?

- Very modern mainland (宇宸、梓涵 style)?

- Or somewhere in between?

This will guide your character choices more than any dictionary definition.

Step 3: Build a small palette of characters

Choose maybe 8–12 characters you like, from reliable, name-friendly categories:

- Virtues / qualities: 安 (peace), 明 (bright), 诚 (honest), 宁 (calm), 睿 (wise), 博 (broad), 毅 (resolute)

- Nature: 林 (forest), 山 (mountain), 雨 (rain), 星 (star), 岚 (mist), 川 (river)

- Gentle abstraction: 诗 (poetry), 宇 (cosmos), 晨 (morning), 澄 (clear), 昕 (dawn)

Avoid extremely rare characters or very complicated ones; they cause trouble in computers and forms.

Step 4: Test combos as whole names, not in isolation

Try combinations and say the full name with surname out loud:

- 李安宁 Lǐ Ānníng

- 王晨星 Wáng Chénxīng

- 陈宇澄 Chén Yǔchéng

Ask:

- Does it flow?

- Any unfortunate homophones with common phrases or slang?

- Does it lean strongly masculine, feminine, or feel neutral? (Check with native speakers.)

Step 5: Sanity-check with real usage

Search the exact 3-character full name in Chinese:

- If you see lots of real people with that name, that’s a good sign of “normality”.

- If you see almost nothing, it might be unique (which can be good or bad).

- If you see a notorious celebrity, meme, or criminal, consider another combination.

Common pitfalls with two-character names (especially for foreigners)

A few mistakes show up again and again in learner-chosen names:

-

Treating it like two isolated words A Chinese given name is a single unit; even if each character has meaning, native speakers read them together, not as a literal two-word phrase. Overly literal combos (“strong soldier”, “little tiger”) can sound childish.

-

Copying trendy names without context Picking something like 奕辰 or 梓萱 because you saw it on a list will make you sound like a mainland Gen-Z kid. If that’s intentional, fine. If you’re 45 and using it as a professional name, it can feel off.

-

Using characters that are only common in transliterations Stacking 艾、欧、奥、茜、娜 purely because you like the sound can accidentally make your name feel like a foreign brand or transliterated English nickname.

-

Ignoring tone and rhythm A name that’s perfect on paper might be awkward when spoken with your surname. Always test the full surname + given name combination out loud.

Two characters, one identity

It’s easy to think of a two-character Chinese given name as “just two nice words”. For native speakers, it’s more like a compressed identity packet:

- a subtle hint about age and region

- a signal of family structure (generation names or not)

- a taste of the parents’ education, aspirations, and aesthetics

- and, of course, the meaning and sound of the characters themselves

That’s why two-character names have become the dominant form: they give just enough space to encode all of this, without turning daily life into a paperwork nightmare.

If you’re choosing a Chinese name for yourself, going with a one-character surname + two-character given name isn’t just “following fashion”. It’s stepping into the shape that most native speakers instinctively recognise as:

“Yes, that looks like a real Chinese name.”

From there, the interesting work begins: deciding which two characters you want to carry around with you, and what kind of story they tell—quietly, every time someone calls your name.

Related Articles

Modern Chinese Names: What Kids Are Actually Called Now

Forget Li Ming and Wang Wei. A ground-level look at what Chinese kids are really named today, what those names signal, and how to sound modern without sounding ridiculous.

Why Most Chinese Name Generators Are Dangerous (Don't Get a Tattoo Yet!)

Before you tattoo a ‘cool Chinese name’ or launch a brand with it, read this. A brutally honest look at how most Chinese name generators actually work — and why they can quietly ruin your skin, your brand, or your reputation.