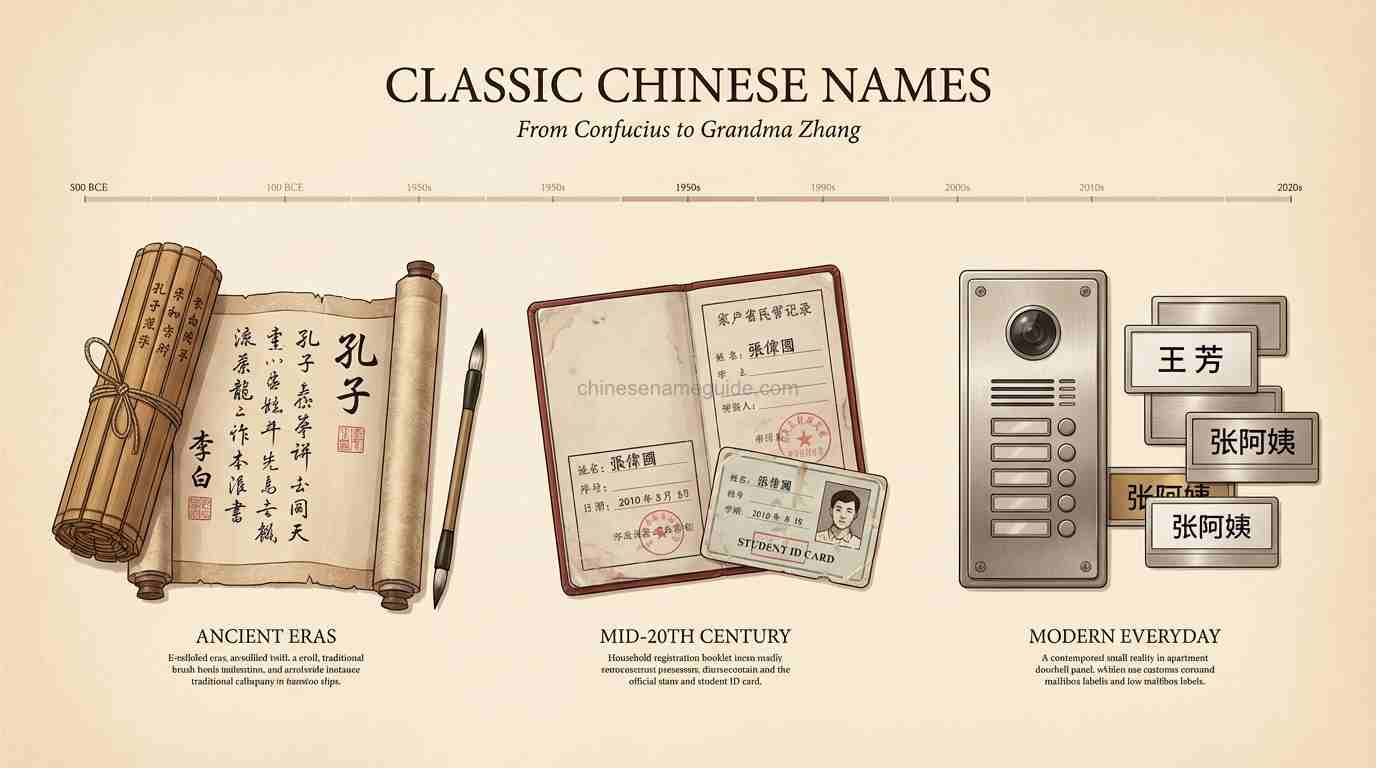

What Counts as a *Classic* Chinese Name? From Confucius to Grandma Zhang

When people say “classic Chinese names”, they might picture Confucius, Li Bai… or Auntie Wang downstairs. This guide unpacks what ‘classic’ really means, how traditional names were built, and how to create a name with an old-school Chinese feel today.

Say “classic Chinese name” to ten different people and you’ll get ten different pictures:

- a bearded sage like 孔子 Kǒngzǐ (Confucius)

- a Tang poet such as 李白 Lǐ Bái

- an 80-year-old auntie called 张秀英 Zhāng Xiùyīng

- or just any name that “sounds ancient” to non-Chinese ears

They’re all right in their own way.

This article is not a baby-name list. It’s a walk through what “classic” really means in Chinese naming:

- how traditional names were structured (姓 xìng, 名 míng, 字 zì, 号 hào)

- how names changed from dynasties → Republic → early PRC

- what makes a name feel old-school to native speakers

- and how you can borrow that flavour without accidentally naming yourself “Duke of the Jade Dragon Phoenix Empire”

“Classic Chinese Name” Actually Means Several Different Things

When non-native learners search classic Chinese names, they often mix together three layers:

- Pre-modern literati names – the people you meet in history books and costume dramas

- Republic & early PRC “old-style” names – your friends’ grandparents and older professors

- Retro-chic “古风 / 古典味” names chosen today because they sound classical

Let’s separate them a bit.

1 Historical literati: ming 名, zi 字, hao 号

In traditional China, a well-educated man was rarely just “Li Something”. A full naming ecosystem surrounded him:

- 姓 xìng – family name / clan surname, comes first

- 名 míng – given name from parents, used in youth or by superiors

- 字 zì (courtesy name) – adult name given around age 20, used among peers in formal contexts

- 号 hào (art name / studio name) – a self-chosen or bestowed “pen name”, often poetic

Using someone’s given name directly in adulthood could be rude; you addressed them by their courtesy name instead. That’s why you see pairs like:

诸葛亮 Zhūgé Liàng (given name) → 字 孔明 Kǒngmíng (courtesy name)

or

李白 Lǐ Bái → 字 太白 Tàibái

Today, when foreigners say “classic name”, they’re often unconsciously reaching for this world: short, dense, elegant names like 玄德 Xuándé, 孔明 Kǒngmíng, 子美 Zǐměi.

2 Republican & early PRC “auntie and uncle” names

Jump to the late 19th–20th century. Courtesy names are fading. Most people now use a simple two- or three-character structure:

[Surname] + [1–2-character given name]

But the vocabulary still feels classic:

- men: 志 Zhì (will), 德 Dé (virtue), 明 Míng (bright), 仁 Rén (benevolence), 国/國 Guó (nation)

- women: 秀 Xiù (elegant), 英 Yīng (outstanding), 玉 Yù (jade), 珍 Zhēn (precious), 淑 Shū (virtuous)

Names like:

- 王德明 Wáng démíng – “virtue + bright”

- 李志强 Lǐ Zhìqiáng – “will + strong”

- 张秀英 Zhāng Xiùyīng – “elegant + outstanding”

- 陈淑芬 Chén Shūfēn – “virtuous + fragrant plant”

To a younger Chinese ear, these names scream “classic auntie/uncle”, not necessarily “ancient poetry” — but for non-natives they still feel very “Chinese classic” compared to trendy 宇宸 / 奕辰 names.

3 Retro-chic “classical flavour” in 2020s naming

Now there’s a new layer: parents who are tired of ultra-popular modern names (奕辰、梓萱、子墨) and deliberately reach backwards for a classical tone.

They might pick:

- single-character given names: 沁 Qìn, 澄 Chéng, 安 Ān

- names with classical particles like 之 (zhī), 若 (ruò), 言 (yán):

- 子言 Zǐyán, 若溪 Ruòxī, 清之 Qīngzhī

- virtue + grace combos that sound “old movie”:

- 德华/德華 Déhuá, 荣慧/榮慧 Rónghuì, 志远/志遠 Zhìyuǎn

These aren’t historical names, but they perform classical Chinese-ness for a modern audience.

How Traditional Names Were Actually Built

Before we talk about “classic-sounding” names for learners, it helps to know how historical names worked structurally.

1 Surname (姓 xìng): the backbone

The “classic” part here is simple:

- same surnames for centuries: 李 Lǐ, 王 Wáng, 张 Zhāng, 刘 Liú, 陈 Chén…

- written first: Li Bai, not Bai Li

The 《百家姓》 Hundred Family Surnames compiled in the Song dynasty starts with 赵钱孙李 Zhào Qián Sūn Lǐ — many Chinese still recognize this rhythm today. A “classic” name almost always rests on one of these familiar surnames, not something invented.

2 Given name (名 míng): short, often one syllable

In pre-modern times, given names were often:

- single characters: 备 Bèi, 羽 Yǔ, 飞 Fēi, 亮 Liàng

- packed with meaning: virtue, nature, aspirations

Later generations (late imperial, Republic) increasingly used:

- two-character given names, but still with a very classical vocabulary:

- 文秀 Wénxiù – cultured + elegant

- 国荣/國榮 Guóróng – national glory

- 玉兰/玉蘭 Yùlán – jade orchid

3 Courtesy name (字 zì): echo, extend, or “answer” the given name

A courtesy name typically:

- appeared at adulthood (around 20), sometimes at marriage for women

- was often two characters,

- was semantically linked to the given name — via meaning, imagery, or homophone.

Classic examples:

刘备 Liú Bèi (given name “prepare/complete”) → 字 玄德 Xuándé (“mysterious/profound virtue”)

孔丘 Kǒng Qiū (Confucius’ given name) → 字 仲尼 Zhòngní (“second son” 仲 + alternative of Ní)

苏轼 Sū Shì → 字 子瞻 Zǐzhān (“one who looks ahead”), → 号 东坡居士 Dōngpō Jūshì (“Resident of Eastern Slope”), his art name

You can feel how short, heavy characters cluster together: 亮、玄、德、孟、伯、子, etc. That’s a big part of the “classical” taste.

Today, ordinary people seldom receive a courtesy name; the system survives in certain traditional circles and in fiction.

The Vocabulary of “Classic”: Characters That Carry an Old-School Aura

Certain characters instantly push a name into “classical” territory for native speakers, even if the person is modern. They’re not forbidden in modern names, but they smell like history.

Rather than giving you a shopping list, let’s look at clusters.

1 Virtue characters: 德、仁、义、忠…

This is the backbone of Confucian-flavoured naming:

- 德 Dé – virtue, moral character

- 仁 Rén – benevolence

- 义 / 義 Yì – righteousness

- 忠 Zhōng – loyalty

- 信 Xìn – trustworthiness

Names like:

- 德仁 Dé rén – “virtue and benevolence”

- 忠义/忠義 Zhōngyì – “loyalty and righteousness”

- 绍德/紹德 Shàodé – “to carry on virtue”

feel heavily classical; you’d see them on generals, scholars, and now older uncles.

2 Scholarly / cultured characters: 文、书、章、雅

These are the names of people who were supposed to read a lot of books:

- 文 Wén – writing, culture

- 书 / 書 Shū – book

- 章 Zhāng – chapter, pattern

- 雅 Yǎ – elegant, refined

- 博 Bó – broad, erudite

Combine them and you get:

- 文博 Wénbó – “broadly cultured”

- 书雅 Shūyǎ – “bookish elegance”

- 雅章 Yǎzhāng – “elegant pattern / chapter”

Even in 2025, these feel old-school in a good way — more library than universe cosplay.

3 Time-and-fate characters: 玄、玄、玄 (yes, really), 悬、若、之

These show up a lot in courtesy names and classical-sounding modern names:

- 玄 Xuán – mysterious, profound

- 若 Ruò – “as if, like” (used decoratively in names)

- 之 Zhī – a classical function word, often used as a “linking” syllable

- 尧 / 堯 Yáo, 舜 Shùn – legendary sage kings (used in given or courtesy names)

Names like:

- 玄德 Xuándé – “mysterious virtue” (Liu Bei’s courtesy name)

- 子若 Zǐruò – “refined one, as if…”

- 清之 Qīngzhī – “purity-of-it” (very literary, almost phrase-like)

To learners, these can feel opaque. To native readers they’re saturated with classical text vibes.

4 Classic feminine grace: 秀、娟、淑、芳、瑶

Women’s “classic” names lean on:

- 秀 Xiù – elegant, refined

- 娟 Juān – graceful

- 淑 Shū – virtuous, gentle

- 芳 Fāng – fragrance

- 瑶 / 瑤 Yáo – lovely jade

Names like:

- 秀兰/秀蘭 Xiùlán – elegant orchid

- 淑珍 Shūzhēn – virtuous and precious

- 琴瑶/琴瑤 Qínyáo – zither + jade

These are the names behind Aunties in Qipao in films — instantly classic, sometimes “dated” if given to a 2025 baby.

Three “Classic Name” Profiles (With Example Sets)

Instead of dumping 100 names, let’s look at profiles. Each describes a type of classic feel you might want, and a few sample names that fit it.

Profile A — “History-book classic”: short, weighty, male

Think: Liu Bei, Cao Cao, Zhuge Liang.

Ingredients

- one-character given name, optionally plus a two-character courtesy name

- masculine virtue or strength: 德, 仁, 勇, 刚, 亮

- monosyllabic, punchy sound

Example sets (surname + given):

赵云 Zhào Yún

- simple surname + nature character “cloud”

- courtesy name 子龙 Zǐlóng (“dragon”), which is where the hero aura comes from

岳飞 Yuè Fēi

- surname “mountain peak” + “to fly”

- courtesy name 鹏举 Péngjǔ (“great bird rising”) – very classical hero naming

If you wanted a modern-but-classic-flavoured version, you might invent:

- 李宪 Lǐ Xiàn – surname Li + “to constitution/order”

- 王衡 Wáng Héng – surname Wang + “balance/measure”

Short, strong, a little austere.

Profile B — “Republic professor classic”: two characters, bookish

Think: elderly professors, grandparents who grew up 1930s–60s.

Ingredients

- two-character given name

- one “virtue” + one “culture/brightness/grace”

- gender marked but not exaggerated

Examples

-

男:

- 陈德明 Chén Démíng – virtue + bright

- 林文彬 Lín Wénbīn – culture + refined wood (彬彬有礼 = courteous)

-

女:

- 王淑芬 Wáng Shūfēn – virtuous + fragrant plant

- 李秀珍 Lǐ Xiùzhēn – elegant + precious

These names feel very “classic Chinese human being” to native speakers. Not ancient, but certainly not modern-internet.

If you’re a non-native who wants to sound solid, mild, and respectful in a professional setting, this is a surprisingly good zone.

Profile C — “Retro-chic classic”: young but 古典味

This is what you see in some 90s–00s kids whose parents liked classical poetry.

Ingredients

- 2-character given name

- at least one obviously literary character (之, 若, 言, 安, 清, 澄…)

- overall gentle, poetic mood

Examples

- 苏清言 Sū Qīngyán – pure + words (could be any gender)

- 阮若水 Ruǎn Ruòshuǐ – “like water” (Daoist vibes)

- 周安之 Zhōu Ānzhī – peace + classical particle (sounds like a poem line fragment)

These names can exist in real life today; they’re stylish, a bit artsy, but not so fancy that they become parody.

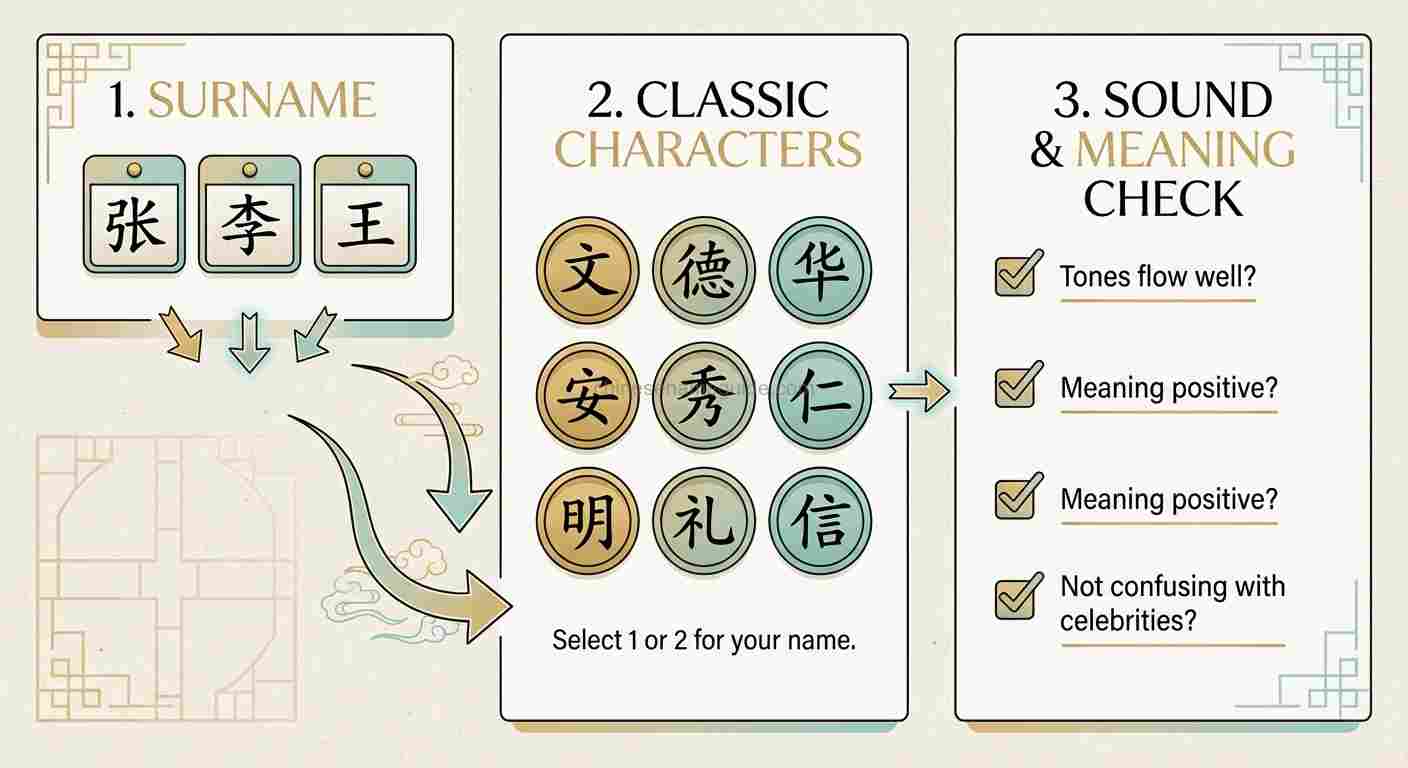

5. If You’re a Learner: How to Give Yourself a “Classic” Chinese Name (Without Going Full Emperor)

Let’s be practical. Suppose you want a Chinese name that feels classic, not hyper-modern — maybe for writing, a language persona, or a less-cringey tattoo.

Here’s a down-to-earth approach.

Step 1 – Pick a conservative surname

Safe, old, everywhere:

李 Lǐ, 王 Wáng, 张 Zhāng, 赵 Zhào, 陈 Chén, 孙 Sūn, 周 Zhōu

If you want a tiny historical nod, 赵钱孙李 (Zhào, Qián, Sūn, Lǐ) are the first four surnames in Hundred Family Surnames — very classic.

Step 2 – Decide which kind of classic

Choose one of the profiles above:

- history-book hero (short, weighty)

- professor-grandparent (virtue + grace)

- retro-chic literary

This prevents you from mixing Yuè Fēi + 梓萱 + Dragon God™ into one Frankenstein.

Step 3 – Build a small character palette

Pick 6–10 characters from one cluster:

- Virtue set: 德, 仁, 信, 义/義, 勤, 勇

- Culture set: 文, 书/書, 博, 雅, 章

- Grace set (feminine-leaning): 秀, 淑, 娟, 芳, 瑶/瑤

- Literary particles: 若, 之, 清, 安, 言, 澄

Then combine them into 1–2 character given names.

Examples (do not copy blindly; they’re patterns, not prescriptions):

- 李文博 Lǐ Wénbó – classic, scholarly

- 王德仁 Wáng Dérén – heavy virtue tone

- 陈清言 Chén Qīngyán – literary, quiet

- 赵淑雅 Zhào Shūyǎ – gentle, old-school feminine

Step 4 – Sanity-check with natives & search

Before you fall in love:

-

Ask a native speaker (or two):

- “What age/generation does this name feel like?”

- “Male, female, neutral?”

- “Normal? weird? trying too hard?”

-

Search the exact characters in a Chinese search engine or social app:

- See if real people use it

- Make sure it’s not the name of a notorious criminal / cheesy dating show meme

You’re aiming for “ah, sounds like my uncle / a character from a serious novel”, not “haha, what is this anime.”

Step 5 – Resist the temptation to add 龙 (dragon), 帝 (emperor), 神 (god)

A single 龙 Lóng is fine in some classic names (赵云’s courtesy name 子龙 is famous). But stacking:

龙神帝尊

into a serious personal name is like calling yourself “Lord King God Emperor” in English. That’s not classical; that’s 14-year-old mobile game energy.

Classic ≠ Frozen in Time

One subtle thing: in Chinese, “classic” isn’t a museum label; it’s a moving target.

- Names from the Tang & Song dynasties feel ancient even to Chinese people.

- Names from your teachers’ and grandparents’ generation feel 老派 (old-school) but also warm and familiar.

- 2020s “retro” names borrow elements of both as style, not as strict tradition.

When you say you want a classic Chinese name, what you usually want is:

something that resonates with the long history, without sounding like a cosplayer or a walking meme to people who actually use the language.

If you keep that in mind — and if you let at least one native speaker veto your wildest ideas — you can absolutely choose a name that feels grounded, respectful, and a little timeless.

And if you ever want help crafting specific options, we can take:

- your real age & context,

- the “profile” you like (hero / professor / retro-literary),

and work out 3–5 candidate names with explanations of which parts are classic, and which parts make them live well in 2025.

Related Articles

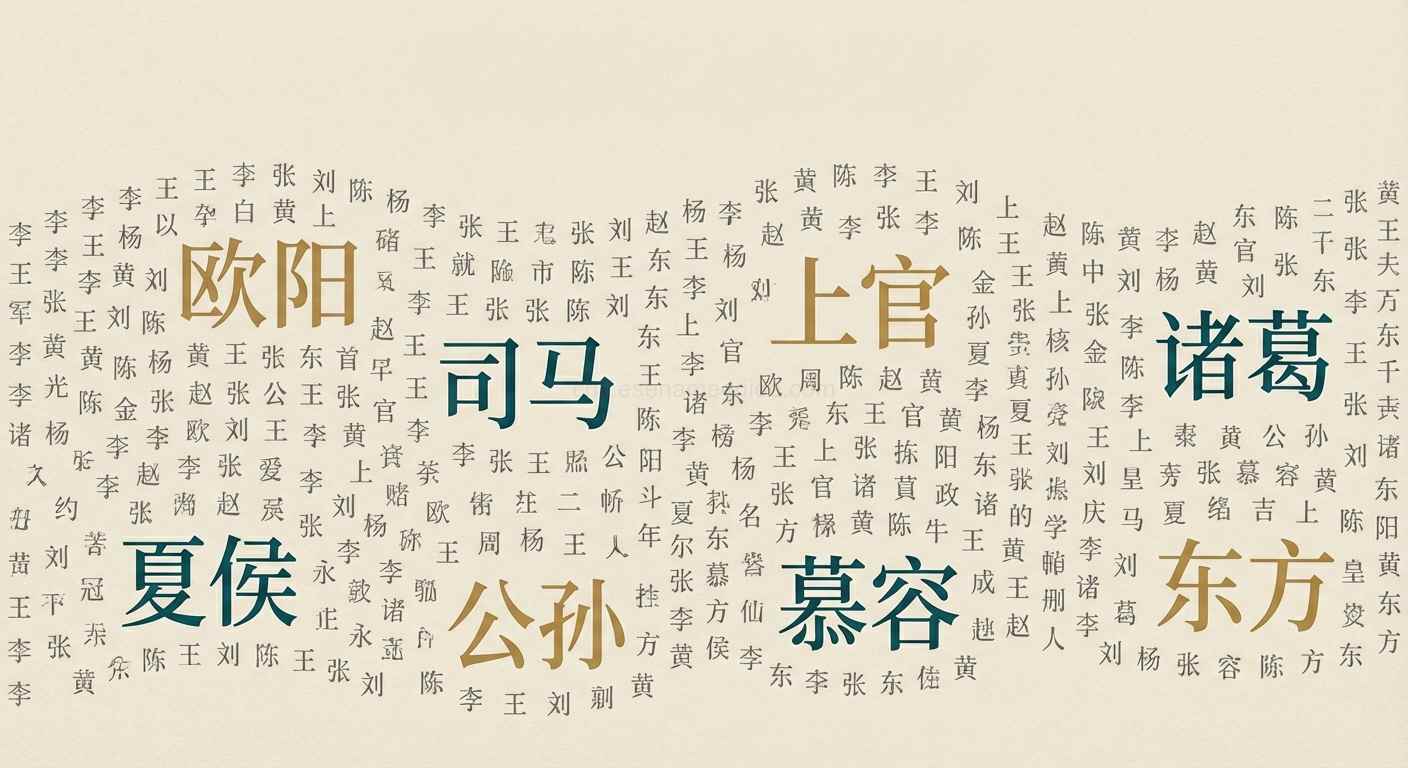

Beyond Li and Wang: The Hidden World of Chinese Compound Surnames (复姓)

Most Chinese surnames are a single character, but a small group of multi-character ‘compound surnames’ preserve traces of ancient titles, clans, and borderland tribes. This guide explains what 复姓 are, where they came from, and what they signal in modern Chinese.

When Your Name Sounds Wrong: Tone, Rhythm, and Ping-Ze in Chinese Names

Meaning isn’t everything. This guide shows how tones, rhythm, and classical ping–ze patterns quietly shape what counts as a ‘good-sounding’ Chinese name—and how non-native speakers can avoid clunky, tongue-twister names.