When Your Name Sounds Wrong: Tone, Rhythm, and Ping-Ze in Chinese Names

Meaning isn’t everything. This guide shows how tones, rhythm, and classical ping–ze patterns quietly shape what counts as a ‘good-sounding’ Chinese name—and how non-native speakers can avoid clunky, tongue-twister names.

Most guides to Chinese names obsess over meaning:

- “Choose characters with good meanings!”

- “Avoid unlucky radicals!”

- “Don’t accidentally call yourself ‘stinky tofu’!”

All true.

But native speakers don’t just read your name—they hear it.

In a tonal language like Chinese,

a name that looks beautiful on paper can still

sound heavy, flat, or awkward in real life

if its tone pattern is off.

This is the part many learners never get told:

Chinese names have prosody—tone, rhythm, and even a faint echo of classical 平仄 píng–zè rules from poetry.

In this article we’ll dig into that hidden layer:

- how Mandarin tones interact inside names

- what “ping–ze” actually is and why it still matters conceptually

- what large name corpora tell us about tone patterns people prefer

- concrete tone combinations to avoid (especially for 3rd tones)

- a step-by-step “sound check” for any Chinese name you’re considering

Names live in sound, not just on paper

Chinese is a tonal language:

standard Mandarin distinguishes words by pitch patterns—the four main tones plus a neutral tone.

That means:

- Same syllable, different tone = different word (

ma1妈 “mom” vsma3马 “horse”) - A name is not just “林雨晴” as written; it’s Lín Yǔqíng as spoken—three syllables, three tones, one contour.

When people judge whether a name is:

- “顺口” (flows nicely)

- “好听” (pleasant)

- or “拗口” (twisty / hard to say)

they’re reacting to the sound pattern:

- the sequence of tones (1–4, plus neutral)

- how those tones alternate between high/low, rising/falling

- and how they interact with tone sandhi rules (especially 3rd tone changes).

Research on Chinese personal names has shown that tone patterns are not random:

in a 1-million-name corpus, tonal patterns of given names cluster strongly around certain combinations, suggesting clear native preferences.

So if you only optimise for meaning and ignore sound, you’re effectively designing a logo without ever looking at the font.

A crash course in tones (only what you need for names)

We don’t need a full phonetics textbook here—just the bits that affect names.

In Mandarin Pinyin, each syllable has a tone number:

- First tone (¯) – high and level (e.g. 妈 mā)

- Second tone (ˊ) – rising, like an English “What?” (麻 má)

- Third tone (ˇ) – low / dipping (马 mǎ)

- Fourth tone (ˋ) – sharp falling (骂 mà)

- Neutral tone – light, unstressed, often on repeats or particles (妈 ma· in 妈妈)

In daily speech, the third tone almost never does a full fall–rise; it tends to be:

- low, when followed by 1st/2nd/4th tone

- converted to a rising 2nd tone before another 3rd tone (the classic 3rd-tone sandhi rule).

Why this matters for names:

- Long chains of 3rd tones (

3–3–3) become a mess of sandhi and sound heavy. - Strings of 4th tones (

4–4–4) can sound like being scolded. - Alternating 1st/2nd vs 3rd/4th often feels more “melodic” and easier to say.

You don’t have to calculate like a linguist.

But you do want to check:

“When I say my full name out loud, what does the tone line look like?”

What on earth is 平仄 (ping–ze), and does it apply to names?

平仄 píng–zè comes from Classical Chinese poetry, not from modern baby-name books. But the underlying instinct—balancing level vs changing tones—is still useful.

1 Ping–ze in classical verse: the original game

In Middle Chinese (the language underlying Tang poetry), tones were classified into four tone classes: 平 (level), 上 (rising), 去 (departing), and 入 (checked).

For verse, poets simplified this into:

- 平 píng – level tone

- 仄 zè – all the other tones (those with more pitch movement)

Regulated verse forms (近体诗) required very strict ping/ze patterns in each line. For example, a couplet might enforce:

- Line 1: 仄仄平平仄

- Line 2: 平平仄仄平

Tone patterns had to mirror and complement each other, creating rhythm and contrast.

Modern Mandarin tones are not identical to Middle Chinese, but broadly:

- 1st & 2nd tones ≈ ping-like (more level / lighter)

- 3rd & 4th tones ≈ ze-like (heavier / more contoured)

2 Ping–ze as a mindset for names

No one is secretly checking your name against Tang-poem rule tables.

But the intuition behind ping–ze does sneak into naming:

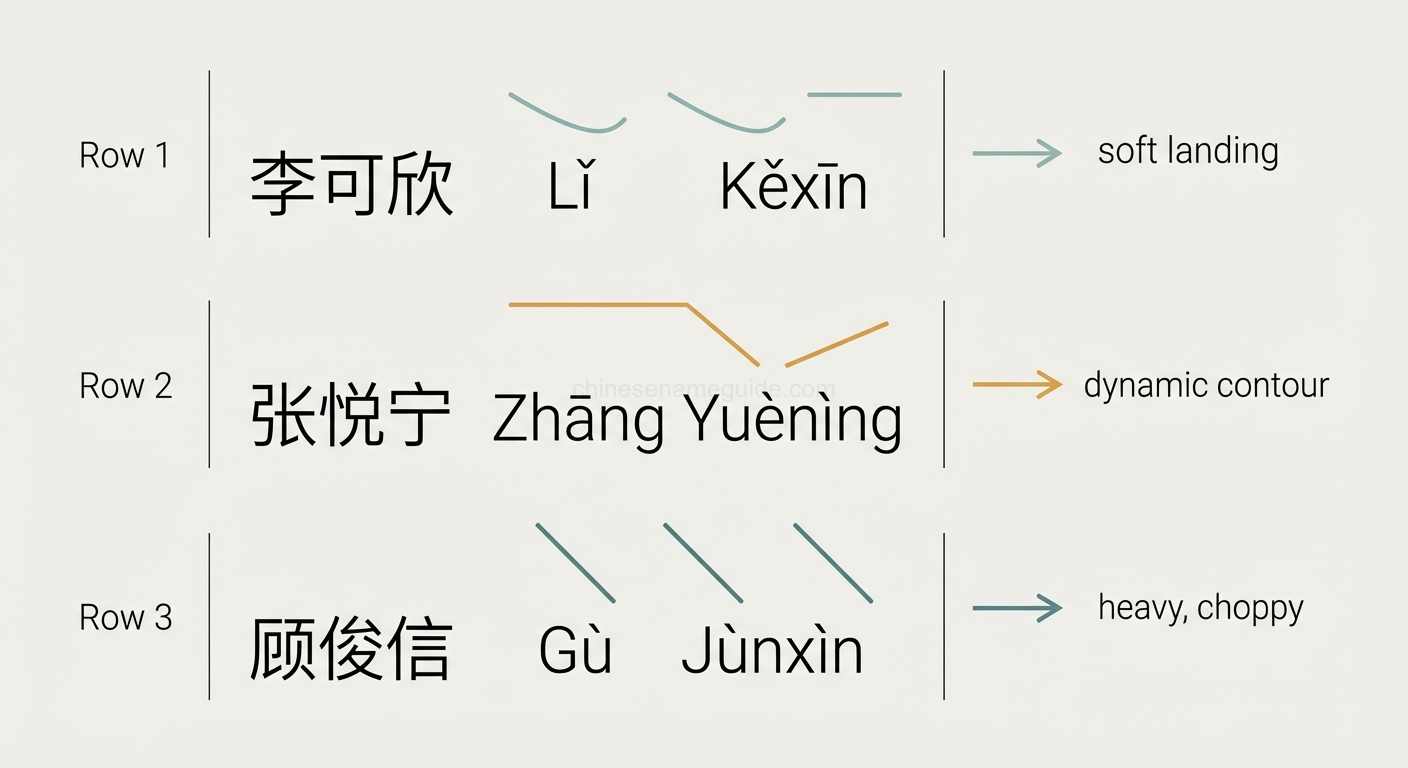

We like contrast between level-ish and dynamic tones

more than monotonous “all flat” or “all heavy” sequences.

So when you look at a full name like:

- 李思远 Lǐ Sīyuǎn →

3–1–3→ ze–ping–ze - 王宇轩 Wáng Yǔxuān →

2–3–1→ ping–ze–ping - 陈静 Chén Jìng →

2–4→ ping–ze

you can think of it as a mini one-line poem:

does it alternate between “smooth” and “kick”, or is it just a row of hammers?

What real data say about tone patterns in names

Several corpus studies have looked at tone distributions in Chinese personal names. Key findings:

- In large corpora (hundreds of thousands to over a million names), tri-syllabic full names (one-character surname + two-character given name) dominate.

- When you classify names by tonal patterns (e.g.

2–3–1,4–2–4), some patterns occur much more often than others. - There is clear evidence of preference, not randomness: people tend to choose names whose tones alternate or balance, and avoid overly “heavy” sequences.

One large study (about 1,000,000 names) analysed tone patterns for surnames + given names and found that:

- Tone information significantly reduces homophone collisions—i.e., tones matter for distinguishing names.

- The distribution of tone patterns in given names is “well regulated”; certain patterns are much more common, and these preferences are relatively independent of the tone of the surname.

We don’t need the exact top-10 patterns to benefit from this. The big takeaways:

- Tone is part of the design space, not an afterthought.

- Native speakers subconsciously gravitate toward certain melodic shapes.

- You can piggyback on those preferences when choosing your own name.

Concrete “sound traps” to avoid in your Chinese name

Let’s get practical. Here are the main ways tone and rhythm can trip you up.

1 Too many third tones in a row

Third tone is the troublemaker.

Rules (simplified):

- Before 1st/2nd/4th tone: 3rd tone is pronounced low.

- Before another 3rd tone: the first one flips to 2nd tone.

So a name like:

Xǐ Yǒu Wěi →

3–3–3

won’t actually be pronounced 3–3–3.

In real speech it turns into a weird chain of low and rising tones and feels muddy and heavy.

Heuristic:

Try to avoid full names where surname + given name produce long 3rd-tone chains.

One 3rd tone is fine. Two in a row is negotiable. Three is asking for trouble.

2 Too many fourth tones (hammer-hammer-hammer)

Fourth tone is sharp and falling. Great for emphasis… in moderation.

Names like:

- Zhào Zhìshì →

4–4–4 - Lì Kuàngnù →

4–4–4

sound like you’re barking commands, not introducing yourself.

Again, one 4th tone is fine, two maybe, three in a row is usually too much unless you want a very forceful, martial vibe.

3 “Flatline” names: all first tones

The opposite problem: names that are all high level tones (1–1–1).

They’re easy to pronounce, but they can feel:

- flat

- a bit childish

- lacking contrast

That doesn’t mean you can’t have a 1–1 given name, just that pairing it with a 2nd/3rd/4th tone somewhere in the full name usually sounds more interesting.

4 Sharp breaks between surname and given name

Because most surnames are fixed, you don’t usually get to choose their tone—but you do choose the given name that follows.

Pay attention to the surname + first given syllable transition:

- If your surname is 4th tone (e.g. Zhào 赵, Xiè 谢), consider avoiding another 4th tone as the very next syllable.

- If your surname is 3rd tone (Lǐ 李, Wǔ 武), maybe don’t start your given name with yet another 3rd tone.

You’re aiming to avoid [heavy][heavy] at the very front of the name.

A simple “ping–ze” checklist for your name

Here’s a minimal system you can actually use.

Step 1 – Write your full name in Pinyin with tones

Example:

林雨晴 → Lín Yǔqíng →

2–3–2欧阳安然 → Ōuyáng Ānrán →1–2–1–2

(For compound surnames, treat the whole thing as surname; we’re interested in the rhythm line.)

Step 2 – Translate tones into “ping/ze-ish”

Roughly:

- 1st / 2nd tones → ping-like

- 3rd / 4th tones → ze-like

So:

2–3–2→ ping–ze–ping1–2–1–2→ ping–ping–ping–ping

Step 3 – Ask three questions

-

Do I have contrast?

- Some alternation between ping-like and ze-like syllables tends to sound more dynamic.

- Example good shapes: ping–ze, ze–ping, ping–ze–ping, ze–ping–ze.

-

Do I have too many heavies?

- Long clusters of ze-like tones (3rd/4th) can feel “压” (crushing).

- If you get ze–ze–ze, consider swapping one character for a ping-like tone.

-

Can I say it 10 times fast without tripping?

- Literally repeat your full name quickly. If your tongue keeps tripping at the same point, something in the consonant/vowel/ tone combo is awkward.

You don’t have to hit some ideal pattern.

You just want to avoid obvious “all ping” or “all ze” flatlines and heavy bricks.

How tone sandhi affects actual pronunciation of names

One more layer: tone sandhi changes how names are spoken in context.

The big ones:

- 3rd + 3rd → 2nd + 3rd (你好 ní hǎo)

- 不 bù (4th) changes to bú (2nd) before another 4th tone

- 一 yī changes tone depending on what follows (yí bàn, yì máo, etc.)

In names, you mostly worry about the 3rd-tone pattern:

- 李勇伟 Lǐ Yǒngwěi (

3–3–3)- in real speech, different speakers may apply sandhi slightly differently,

- but everyone feels it’s harder to say than, say, 李文伟

3–2–3or 李勇威3–3–1.

Also, when a character is reduplicated in nicknames (e.g. 冰冰, 晶晶), the second syllable often takes a neutral tone in casual speech, even if it’s lexically 1st/2nd/3rd/4th.

Moral: don’t over-optimise based on the textbook tones alone;

imagine how people will actually say the name quickly.

Balancing sound and meaning: a design workflow

Here’s a workflow that keeps meaning, sound, and ping–ze all in play.

1. Start with meaning + character shortlist

Make a shortlist of characters you like for semantic reasons:

- Values: 安 (peace), 宁 (calm), 诚 (sincere), 睿 (wise), 勇 (brave)

- Imagery: 林 (forest), 星 (star), 澄 (clear), 晨 (morning), 雨 (rain)

Check that they’re:

- common enough to be recognisable,

- without nasty slang meanings,

- not over-complicated graphically.

2. Combine them into 1–2 given names you like on paper

For example:

- 宇安, 星澄, 雨宁, 睿晨, 安澄…

Don’t worry about tones yet; just get some meaningful combos.

3. Now do the tone + ping–ze pass

For each candidate:

-

Add Pinyin with tones.

-

Write out the full name including surname.

-

Look at the tone pattern:

- Does it mix ping-like and ze-like tones?

- Do you have long runs of 3rd/4th tones?

- Does surname + first given syllable create a

[heavy][heavy]start?

Adjust by:

- swapping out one character for another with a more suitable tone (often you can keep similar meaning but change tone),

- or reordering characters if that still feels natural.

4. Sanity-check with a human (and ideally a dialect)

If possible, ask:

- one Mandarin native speaker

- and someone from the region whose accent you care about (e.g. Cantonese, Taiwanese Hokkien)

Why dialect?

The same characters can have different tone contours and sound symbolism in other Sinitic languages.

You don’t need to optimise for every dialect on earth, but if all your close friends are Cantonese, it’s worth checking that your carefully tuned Mandarin tone pattern doesn’t become “雷声大雨点小” in Cantonese.

Quick reference: tone-aware name checklist

When you’re about to lock in a Chinese name, run this checklist:

- Pinyin + tones written clearly for the full name.

- No long chains of 3rd tones (especially at the start).

- No triple 4th tones unless you really want a super-forceful feel.

- At least some alternation between level-ish (1st/2nd) and heavier (3rd/4th) tones.

- Surname + first given syllable doesn’t create a jarring

[heavy][heavy]punch. - Say it out loud 10 times—if you keep stumbling, reconsider.

- One native speaker says it sounds “顺口” (flows) without grimacing.

If you pass all of that and still love the meaning, you’re in very good shape.

The bottom line: your name is a three-syllable song

Choosing a Chinese name isn’t just about avoiding unlucky radicals or bad puns.

It’s about crafting a tiny piece of music you’ll hear for the rest of your life.

- The characters carry your story in writing.

- The tones and rhythm carry your story in sound.

- Classical ping–ze rules don’t literally apply,

but the instinct behind them—balancing level and oblique, tension and release—still shapes what sounds right to native ears.

If you give your name even half as much attention for sound as you do for meaning, you’ll avoid the common traps:

- “too heavy”,

- “too flat”,

- “too twisty to say fast”.

And instead, you’ll end up with something that feels like a short, satisfying line of poetry—the kind people like to say, and remember.

That’s when you know your Chinese name doesn’t just look right.

It sounds like it belongs.

Related Articles

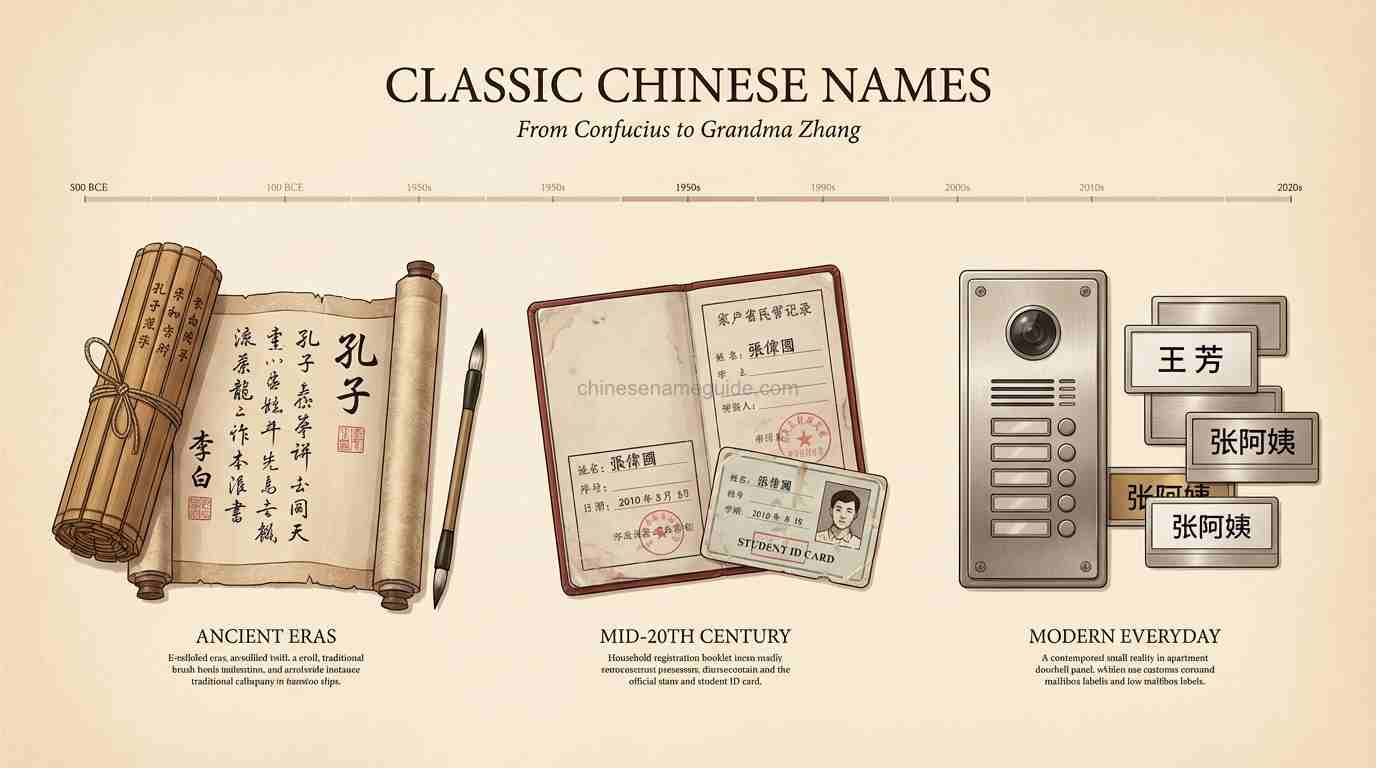

What Counts as a *Classic* Chinese Name? From Confucius to Grandma Zhang

When people say “classic Chinese names”, they might picture Confucius, Li Bai… or Auntie Wang downstairs. This guide unpacks what ‘classic’ really means, how traditional names were built, and how to create a name with an old-school Chinese feel today.

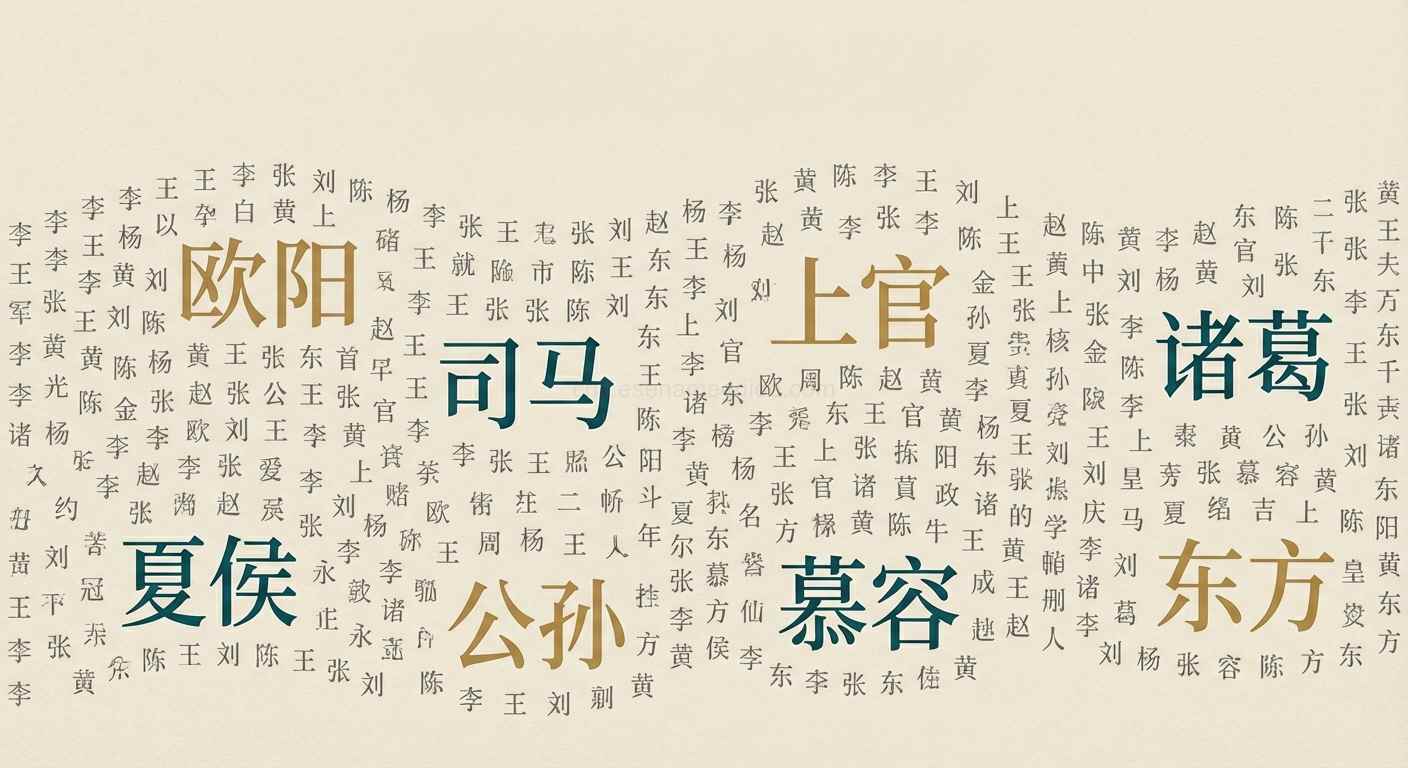

Beyond Li and Wang: The Hidden World of Chinese Compound Surnames (复姓)

Most Chinese surnames are a single character, but a small group of multi-character ‘compound surnames’ preserve traces of ancient titles, clans, and borderland tribes. This guide explains what 复姓 are, where they came from, and what they signal in modern Chinese.