When Your Chinese Name Is Just Your English Name in Characters

An in-depth look at Chinese names that are pure transliterations of English names—how they’re built, how native speakers perceive them, and when they’re useful or risky.

If you’ve taken any beginner Chinese class, you’ve probably met them:

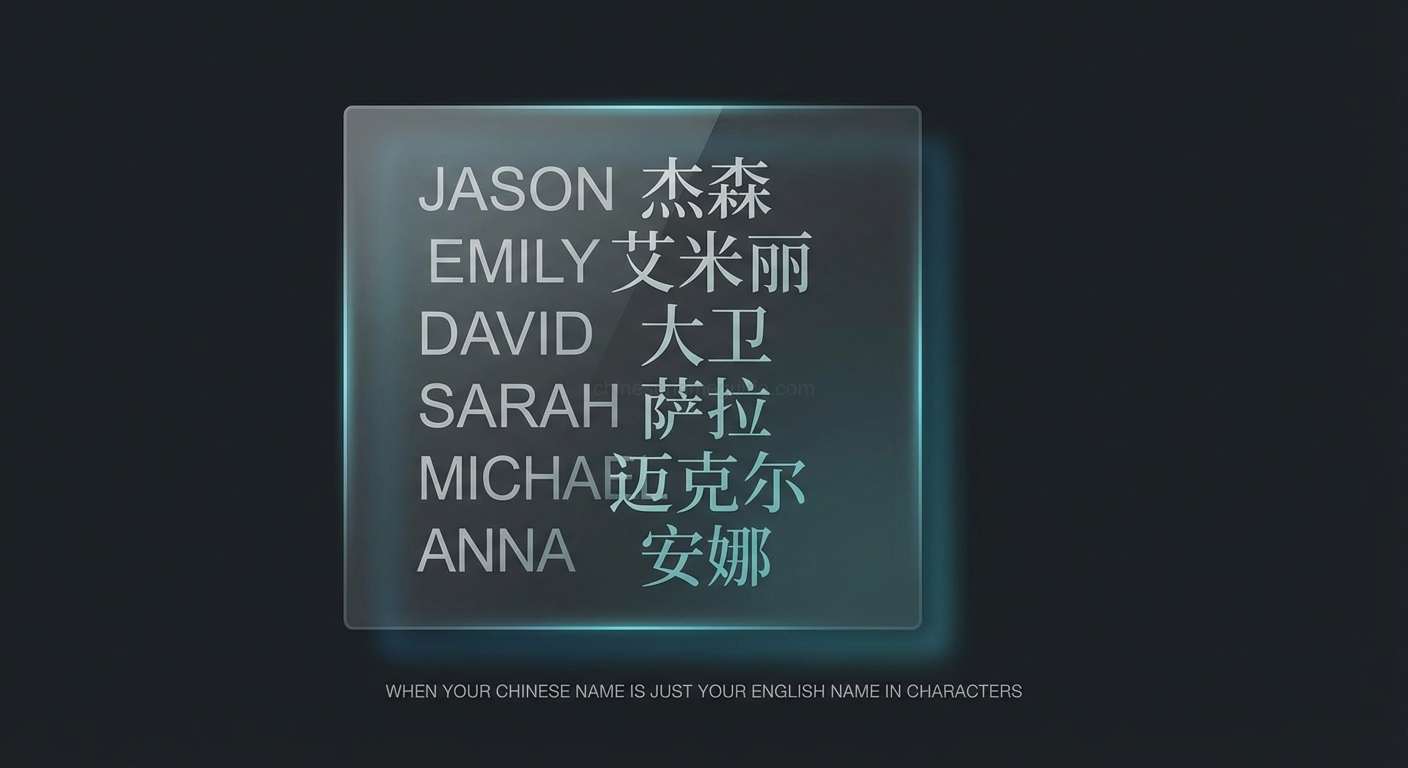

Amy → 艾米 Emma → 艾玛 Kevin → 凯文 Jason → 杰森 David → 大卫 / 戴维

They look like Chinese names. They sound roughly like the English originals. They’re easy to remember. And for a while, they feel like your Chinese name.

But here’s the key point:

These names were not designed as “real Chinese names”. They’re phonetic labels, built to shadow an English name.

This doesn’t mean they’re “wrong”. It does mean they have limits.

In this article we’ll unpack those limits and possibilities:

- what “pure transliteration” actually means

- where these names came from

- how native speakers read them (very differently from how you do)

- when transliterated names are totally fine

- when they quietly work against you

- how to move from “just a shadow of my English name” to a Chinese identity you can actually grow into

What Do We Mean by “Purely Transliteration-Based Chinese Names”?

Let’s define the target.

When we say purely transliterated Chinese names, we mean names that:

- are built by matching English sounds with similar-sounding Chinese syllables

- ignore Chinese naming culture (gender markers, era, meanings, register)

- exist primarily so that an English name can be written and read in Chinese, not as a standalone Chinese identity

For example:

- Emma → 艾玛 Ài-mǎ

- Amy → 艾米 Ài-mǐ

- Kevin → 凯文 Kǎi-wén

- Jason → 杰森 Jié-sēn

- Jack → 杰克 Jié-kè

- Michael → 迈克 / 麦克 Mài-kè

Every character here acts like a sound container. Its meaning is almost an accident.

No one chose “艾” for its “mugwort herb” meaning when naming Amy. It was picked because ài feels close to “A-”, and “米” (mǐ) is convenient for “-my / -mee”.

If you’re used to English names, this is normal: we don’t pick “Kate” because we love the meaning of “pure”; we pick it because we like the sound and association. But in Chinese, that’s not how native naming usually works.

Why Do Transliteration-Based Chinese Names Exist at All?

There are three big reasons they’re everywhere.

1 Media needs a way to talk about foreign people

News, subtitles, novels, and Wikipedia have to name:

- foreign politicians

- movie stars

- fictional characters

- historical figures from other languages

They need a standard written form in Chinese that:

- is pronounceable

- approximates the original sound

- is easy to reproduce in print and databases

That’s where transliteration shines. “Taylor Swift” doesn’t need a poetic Chinese name full of cultural symbolism. She needs a consistent label so that all Chinese media are talking about the same person.

2 Systems and documents need stable mappings

Databases, immigration systems, translation engines and search algorithms all care about mapping:

one person ↔ one English name ↔ one Chinese string

A phonetic transliteration such as “凯文 Kevin” is easy to:

- index

- search

- reverse-map

Whether the characters form a “good Chinese name” is irrelevant to the system. It’s just a cross-language handle.

3 Language teachers need fast, low-risk “Chinese names”

On the first day of class, a Chinese teacher might be facing 20–30 students:

“Let’s all have a Chinese name!”

The teacher has:

- limited information about you

- limited time

- zero guarantee that you want a deep, permanent Chinese identity

So the safest and fastest move is just:

- Emma → 艾玛

- Ben → 本

- Lisa → 丽莎

- David → 大卫

It:

- keeps everyone’s English ↔ Chinese mapping clear

- avoids the cultural landmines of designing proper Chinese names on the fly

- lets people start using Chinese labels without delay

For short-term classroom use, that’s perfectly reasonable.

The Building Blocks: “Sound Container” Characters

If you look at dozens of transliterated names, you’ll see the same characters again and again. They’re not “transliteration characters” by definition, but they’ve become a familiar toolkit.

A few examples:

-

艾 (ài) – often used for names starting with “A-”:

- Amy 艾米, Emma 艾玛, Allen 艾伦

-

安 (ān) – also used for “Ann / An-” sounds, with a softer meaning:

- Anna 安娜, Andy 安迪

-

凯 (kǎi) – used for “Ke- / Kay- / Kai-”:

- Kevin 凯文, Kay 凯, Kyle 凯尔

-

杰 (jié) – used for “J-” names:

- Jason 杰森, Jack 杰克, Jerry 杰瑞

-

克 (kè) and 斯 (sī) – universal end-pieces:

- Nick 尼克, Mark 马克, Chris 克里斯, James 詹姆斯

Over time, native readers develop a radar:

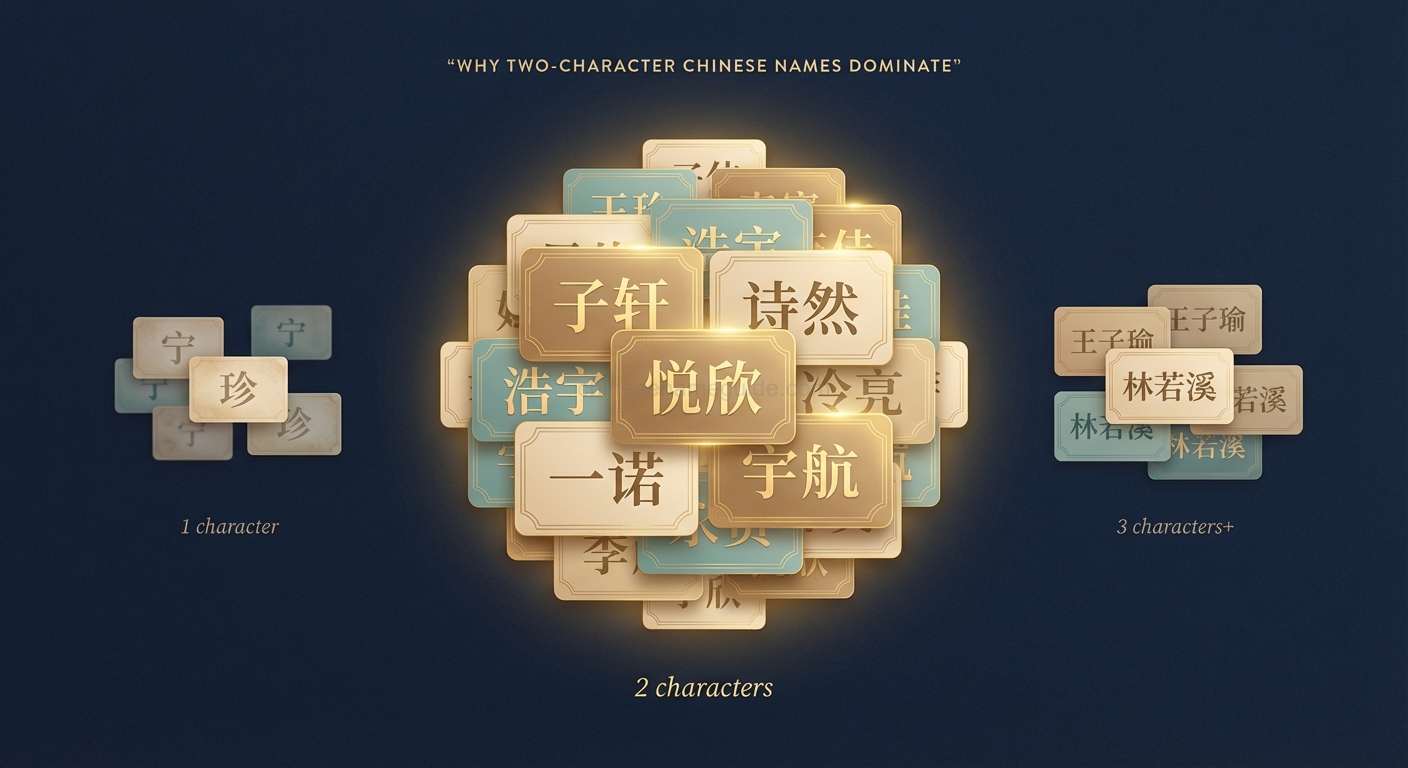

A short 2–3 character name packed with 艾 / 欧 / 奥 / 斯 / 克 / 娜 / 茜… almost always reads as “foreign name in transliteration mode”, not as “Chinese parents named their kid this”.

That distinction matters when you start using such names as if they were native-style names.

How Native Speakers Actually Perceive These Names

Let’s split this into a few contexts.

1 On TV, in news, in subtitles: completely normal

When Chinese people see:

- 拜登 (Biden), 特朗普 (Trump)

- 艾玛·沃森 (Emma Watson)

- 杰森·斯坦森 (Jason Statham)

they don’t judge those strings as “good names” or “bad names”. They treat them as:

technical solutions for “we need to write foreign names in Chinese”.

No one expects Biden to have a culturally meaningful Chinese given name. They expect a consistent tag.

The same goes for “Amy” as 艾米 when describing a foreign friend in a story.

4.2 For foreign classmates and colleagues: neutral to friendly

If you introduce yourself as:

“I’m Jason. In Chinese, you can call me 杰森.”

Most Chinese people will think:

- “Great, I know how to say and write that.”

- “He’s clearly not Chinese, this name matches that.”

As long as the setting is casual—classroom, office, WeChat friend list—this is absolutely fine.

4.3 As a formal “Chinese identity”: a bit off

The friction starts when you present a raw transliteration as:

- your only “Chinese name”, and

- you want it to function like a normal Chinese name.

For example:

- publishing a Chinese essay under the name “杰森”

- running a company in China under “凯文工作室”

- getting a tattoo of “艾米” because “that’s my Chinese name”

For native speakers, this can feel slightly similar to:

a Chinese person in the US insisting their official English name is “ZHANG WEI” (in caps, pinyin, no adaptation) and never uses any English given name.

It’s not wrong, but it silently signals:

- “I haven’t really entered the naming culture of this language.”

- “I’m still standing outside, with my original name wrapped in phonetics.”

If you want to keep a healthy distance from Chinese culture, that’s fine. If you want to inhabit the Chinese language more deeply, it’s a missed opportunity.

Why Transliteration Names Are So Attractive (The Real Advantages)

Let’s be fair. There are good reasons they’re popular.

1 Memory and mapping are effortless

You don’t have to remember that:

- English = “Emily”

- Chinese = “许语晴”

- Japanese friends call you something else

- and your passport uses yet another spelling

Instead, “Emily → 艾米丽” is almost one-to-one. Your brain doesn’t suffer.

2 Documents and cross-language workflows are easy

On résumés, visas, conference name badges, or academic publishing, having:

Kevin Smith / 凯文·史密斯

is much easier to manage than:

Kevin Smith / 林恺文

if nobody knows that “林恺文” is you.

3 Low cultural risk in low-stakes contexts

Genuine Chinese-style names can go wrong in dozens of ways:

- unfortunate puns

- accidental sexual slang

- strong regional / generational flavour

- sharing a name with an infamous celebrity or meme

Most teachers don’t have time to run full cultural QA on a name for each student. A simple transliteration is safer by default for short-term use.

So if your relationship to Chinese is:

- a one-year language program

- some tourism

- a few work trips

then “凯文 / 艾米 / 杰森” is probably all you need.

The Hidden Costs: What You Lose When You Stay with Pure Transliteration

The problem appears when you cross an invisible line:

You want Chinese to be a long-term part of your life, but your Chinese “name” is still just a phonetic label.

Here is what you lose.

1 You gain zero “Chinese information”

A typical Chinese given name tells native readers a surprising amount:

- gender-ish vibe

- rough generation

- some guess at personality, values, or the parents’ taste

For example, names that end in:

- –芳 / –娜 / –静 / –婷 lean feminine

- –强 / –军 / –伟 / –磊 lean masculine

- early PRC names may have “nation / red / army / construction” motifs

- 2000s kids might have “universe / star / dawn / rain” motifs

Your name might suggest “bookish”, “household middle-class”, “rural 1950s”, “urban Gen Z”, “internet novel fan”, etc.

By contrast, 凯文 or 艾米 communicates almost nothing except:

“This person has a non-Chinese name in Latin letters.”

No gender nuance, no generational feel, no values. It’s flat.

2 Many phonetic characters are rarely used in native names

Characters like:

- 艾, 欧, 奥, 茜, 娅, 斯, 克

are totally legitimate characters, but in the mental map of a native speaker they live mostly in:

- transliterated brand and place names

- transliterated foreign personal names

- niche vocabulary

When you stack them into a “name”, it often reads as:

“Probably not a Chinese person, and definitely not a traditional Chinese naming style.”

Again, that may be exactly what you want. But if you were hoping for “I blend in naturally in Chinese”, it doesn’t give you that.

3 In serious contexts, it can look lazy or superficial

Imagine these situations:

- You publish a serious book in Chinese under the name “杰森”.

- You launch a service for Chinese clients and your only Chinese name is “凯文老师”.

- You say you want to live long-term in China or Taiwan, but after 10 years, you still use only a bare transliteration.

Nobody is going to scold you. But some people will quietly read it as:

“You never cared enough to fully enter this culture’s naming system.”

That doesn’t mean you must go full “ancient scholar name”. It does mean that investing a bit more can pay off in respect and connection.

Can You Have the Best of Both Worlds? (Yes: Hybrid Solutions)

You don’t have to choose between:

- pure transliteration, or

- completely unrelated Chinese name

There’s a middle path: hybrid or layered naming.

1 Keep a soft echo of your English name, add real Chinese structure

Let’s say your name is Emma and your classroom name is 艾玛.

You could:

- pick a normal Chinese surname: 李, 王, 陈, 林, etc.

- design a given name that:

- is easy for you to connect to Emma

- but also has meaning, gender feel, and a natural tone in Chinese

For example:

- 怡玛 Yímǎ – “pleasant / joyful + ma”

- 依玛 Yīmǎ – “rely on / gentle + ma”

- 艳玛 Yànmǎ – “bright, vivid + ma” (more flamboyant)

Maybe you become:

Formal Chinese name: 王怡玛 Wáng Yímǎ Nickname among classmates: 艾玛

Native speakers will see 王怡玛 as an actual Chinese-style name. You will still feel the echo of Emma inside it.

2 Let the English inspire the meaning, not copy the sound

Suppose your name is Grace.

Instead of 格蕾丝 (pure transliteration), you could ask:

- What does “Grace” mean to me?

- kindness, elegance, Christian grace?

Then choose characters that lean into those meanings:

- 恩雅 Ēnyǎ – grace / kindness + elegant

- 雅恩 Yǎ’ēn – elegance + grace

- 慧恩 Huì’ēn – wisdom + grace

These names don’t sound like “Grace” anymore. But they are Grace, in Chinese.

3 Have two names on purpose: a “file name” and a “stage name”

Many Chinese people already do this in reverse:

- passport: ZHANG WEI

- English life: Michael Zhang

You can mirror that:

- In English contexts: “Kevin Smith”

- In bureaucratic or technical Chinese contexts: 凯文·史密斯 (simple transliteration)

- In Chinese-speaking life (friends, projects, online persona): 林恺文, 高文凯, or some other properly designed Chinese name

They co-exist. One helps machines and paperwork. The other is for humans.

“But I’ve Been Using 凯文 / 艾米 for Years. Do I Have to Change?”

Short answer: no. You don’t have to “fix” anything.

The longer answer is: it depends what you want next.

Transliterated names are perfectly fine if:

- your contact with Chinese is light or temporary

- you only need something your teacher and classmates can say and write

- you like the sound and don’t expect more from the name

They become limiting if:

- you’re building a long-term presence in Chinese (content, business, community work)

- you want your name to “belong” in the language, not just hover above it

- you care about how your identity feels to native speakers, not just how it maps for yourself

If you’re in the second group, a gentle “upgrade” can be worth it.

You might:

- Keep your old transliteration as a nickname, especially with older friends.

- Introduce a new, Chinese-designed name as your formal Chinese identity.

- Publicly write about the change (“I used to be 凯文; here’s why I became 林恺文”). That story itself can be a bridge to your audience.

A Quick Decision Guide: Transliteration vs. Full Chinese Name

Ask yourself three questions:

-

How deep is my relationship with Chinese?

- 1–2 semesters / tourism / casual hobby → transliteration is enough.

- long-term life, work, or creative career → consider a real Chinese name.

-

Who will see this name, and where?

- only classmates & WeChat friends → anything pronounceable is fine.

- book covers, client contracts, CVs, film credits → invest in something that stands on its own.

-

What do I want this name to do?

- simply “point at me across languages”? (like a label on a box)

- or “carry part of my story inside Chinese”?

A pure transliteration is excellent at the first job. It’s very weak at the second.

The Core Idea to Take Away

Transliterated Chinese names are not evil. They’re shadows: flat shapes cast by your English name onto the wall of another language.

For some purposes, a shadow is all you need.

But if you want a place to live inside Chinese—a name that can grow with you, be read and felt by native speakers, and sit comfortably next to their own names—you eventually need more than a shadow.

You don’t have to abandon your English name. You don’t even have to abandon your beloved 艾米 or 凯文.

You just have to decide:

“Is Chinese a hallway I’m walking through, or a room I plan to furnish and stay in?”

If it’s the second, then building a real Chinese name, not just a transliteration shell, is one of the most powerful—and surprisingly fun—steps you can take.

Related Articles

Modern Chinese Names: What Kids Are Actually Called Now

Forget Li Ming and Wang Wei. A ground-level look at what Chinese kids are really named today, what those names signal, and how to sound modern without sounding ridiculous.

Why Most Chinese Name Generators Are Dangerous (Don't Get a Tattoo Yet!)

Before you tattoo a ‘cool Chinese name’ or launch a brand with it, read this. A brutally honest look at how most Chinese name generators actually work — and why they can quietly ruin your skin, your brand, or your reputation.