Why Most Chinese Name Generators Are Dangerous (Don't Get a Tattoo Yet!)

Before you tattoo a ‘cool Chinese name’ or launch a brand with it, read this. A brutally honest look at how most Chinese name generators actually work — and why they can quietly ruin your skin, your brand, or your reputation.

Let’s start with a very real scene.

You:

“I want a Chinese name for a tattoo / my brand / my game nickname. I’ll just google ‘Chinese name generator’, click the first result, and copy-paste whatever comes out.”

Two minutes later you have something like:

艾炫龙 · Ai Xuanlong

It looks… powerful? There’s fire, there’s a dragon, the font preview is 🔥. You’re half a step away from sending it to the tattoo artist.

Here’s the uncomfortable truth:

That name might look cool to you, but to native speakers it can be: childish, cringe, nonsensical, or accidentally hilarious.

And once it’s on your skin or your logo, you don’t get to add a footnote explaining “haha it’s from a random website that mashed some characters together.”

This article is a reality check before ink hits skin (or before a domain goes live):

- what most “Chinese name generators” are actually doing under the hood

- common ways they quietly generate ugly / awkward / dangerous names

- why tattoos and long-term branding are a worst-case scenario

- a safer workflow if you do want to use tools

- a quick “Tattoo Checklist” to stop preventable disasters

What Most Chinese Name Generators Actually Do

On the surface, name generators look magical:

“Type your English name → get instant Chinese name!” “Click ‘cool style’ → receive 20 badass characters!”

Under the hood, most of them are not doing deep linguistics or cultural checks. They’re usually one of three simple machines.

1 Phonetic blender: “Emma” → 艾玛 and friends

The simplest type just tries to imitate the sound of your English name using Mandarin syllables.

- Emma → 艾玛 (Ài mǎ)

- Jason → 杰森 (Jié sēn)

- Kevin → 凯文 (Kǎi wén)

This can be fine for:

- movie credits

- import/export company contact lists

- just having a “Chinese version” of your name for convenience

But problems appear when you treat this as:

- a Chinese tattoo

- a pen name / character name

- an “I want a deep, meaningful Chinese persona” situation

Because:

- 艾玛 is basically “Eh-mah”. It doesn’t secretly mean “gentle forest goddess of the east wind”.

- 杰森 is just “Jay-sen” in character form, not a carefully crafted Chinese identity.

You’re borrowing the sound, but not getting a culturally grounded name.

For some contexts, that’s okay. For permanent ink, it usually isn’t.

2 Character salad: random “nice words” in a bowl

The second common type of generator takes a bunch of “positive” characters and:

- throws your gender / personality into a few if-else rules

- randomly combines characters that mean things like dragon / noble / star / wise / ocean

- enforces rough syllable counts (“2 characters = cool male”, “soft vowels = cute female”)

- spits out names until the page looks full

The output looks sophisticated because:

- each character alone can be explained positively

- the Pinyin under each name gives you something to say out loud

- maybe there’s a fake “luck score” or “five elements rating”

What this type usually does not do:

- check if that combination is actually used as a real personal name

- check if it sounds like a mobile game NPC, a 12-year-old’s username, or a soap opera villain

- check for weird idioms, slang, or unfortunate homophones

- check regional flavor (Mainland vs Taiwan vs Hong Kong vs overseas usage)

So you end up with things like:

- 炫龙 (Xuànlóng – “show-off dragon”) → sounds like the name of a 2008 browser game

- 冰殇 (Bīngshāng – “ice + bereavement”) → edgy emo novel, not a regular human

- 圣帝 (Shèngdì – “holy emperor”) → nobody sane names their kid this in real life

These names might be fine as ironic game handles. They are terrible as tattoos or serious public identities.

3 Pseudo-mystical numerology machines

The third category looks “deep” because it references:

- 五行 (five elements)

- 八字 / 四柱 (birth chart)

- strokes, element balance, lucky numbers

…then quietly slaps those onto random characters pulled from a list.

The logic is often:

- find characters with stroke counts that make a “lucky pattern”

- ensure each character is classified as wood / fire / earth / metal / water in some table

- combine them into any sequence that looks name-like

What’s missing?

- serious linguistic checks (is this pronounceable and natural?)

- register & gender (does this sound like a real name or a Daoist spell?)

- era (does this sound like a 17th-century poetry hermit or a 2024 baby?)

- basic sanity (does this combination read as tragic, creepy, or comically over the top?)

You can absolutely use real 五行 / 八字 practitioners to refine a good name. But if you start from a linguistically bad name and “bless” it with fake numerology, it’s still a bad name — just with extra candles around it.

Why This Becomes Dangerous for Tattoos & Branding

Let’s be honest: if you generate a goofy name and only use it as a throwaway game ID, the stakes are low.

But tattoos, brand names, artist names, or pen names are different:

- You’re stuck with them (or pay a lot to change them).

- You’re showing them to people who can actually read Chinese, not just your English-speaking friends.

- You might be putting them in contexts where you will never get to explain “it came from a random website”.

Here’s how generator-names go wrong in practice.

1 Meaning that collapses when put back into real Chinese

A typical generator might produce:

烁灵 (Shuòlíng) – “sparkling spirit” (in their English explanation)

To a native speaker, depending on context, it can feel:

- vaguely game-ish, like a pet in a mobile RPG

- overly dramatic, cliché fantasy style

- not wrong, but definitely not “deep”.

Now imagine that on your forearm in brush-stroke script, forever.

Another example:

暗雪 (Ànxuě) – “dark snow”

Poetic? Maybe, if you’re writing a fantasy novel. On a real living person from Europe/US, without context, it’s pure edgy teenager fanfic energy.

2 Names that scream “I don’t know how Chinese names work”

Some tells that a name is generator-born:

- stacking multiple super-rare characters that most Chinese people can’t even read

- mixing simplified and traditional forms in one name for no reason

- using characters that are basically never used in names but look dramatic (like random Buddhist or Daoist jargon)

- sounding exactly like a Xianxia webnovel protagonist but being used as a legal/business name

You’re basically walking around with a sign that says:

“This looked cool to me in a font preview, but I never asked anyone who actually uses this language.”

If you’re okay with that, fine. If you want respect from Chinese readers, it’s a problem.

3 Ignoring gender, age, and era

Most generators don’t understand:

- gendered patterns (花/芳/娜/娟 vs. 龙/刚/强/伟 types of characters)

- generational style (names popular in the 1960s vs 2020s)

- whether something feels like a baby name, a grandparent name, or an internet nickname

So you might get:

- a name that reads as grandma in a county town on a 22-year-old tattooed musician

- a name that screams teenage MMO player on a 40-year-old consultant

Chinese people do make these “huh?” judgments in a split second, the same way you do when you meet an English speaker named “Moonblood Shadowfax” in a board meeting.

4 Branding disasters: un-searchable, un-typeable, un-printable

Many generator names are:

- built from rare characters that break on some systems

- hard to input, because they’re not in the first pages of IME suggestions

- close to unfortunate existing phrases or brand names

Imagine:

- your logo uses a character that your own Chinese staff can’t type without copy-paste

- your brand name is one typo away from a rude slang term or a famous scam company

- your WeChat account constantly has to explain “no, it’s the other ‘xuan’, the one with 23 strokes”

Generators usually don’t check for:

- frequency (how common a character is)

- collisions with major brands or notorious names

- whether your chosen combo gets Google/Baidu results you don’t want

For a brand, that’s not just “cringe”; it’s money and trust lost.

Red Flags: How to Tell a Generator Name Is Probably Bad

If a tool gives you a name, and any of these are true, treat it as red flag:

-

No explanation in Chinese You only get a vague English blurb (“represents happiness and success”). A serious tool can at least show basic word usage of the characters in real Chinese.

-

Everything sounds like a fantasy novel protagonist If every male name includes 龙 (dragon), 天 (heaven), 帝 (emperor), 神 (god), or 狱 (hell)… run.

-

Too many ultra-complex characters Both characters are 20+ strokes? Cool for calligraphy posters, terrible for everyday writing and data entry.

-

Lots of mixed script One character is simplified, the other is traditional, and there’s no regional reason. It’s a visual mess and a cultural tell that nobody thought this through.

-

Same pattern repeated for every user You notice names look like [Element + Dragon] or [Poem + God] for everyone. It’s template spam, not personalization.

-

There’s a random “luck score” but no linguistic information If they tell you “92% auspicious!” but nowhere mention tones, commonness, or gender/era feel, you know what the priority is.

-

You paste the name into a Chinese search engine and see almost nothing Zero real people, zero natural phrases, just other generator pages? That’s a sign this is not a natural, lived-in name.

Safer Ways to Use Generators (If You Insist)

All that said, tools aren’t useless. The problem is treating them as Oracle of Truth instead of brainstorming assistants.

Here’s a saner way to use any generator:

-

Use it as an idea dump, not a verdict

- Collect 5–10 candidate names you kind of like.

- Focus on characters that repeatedly attract you.

-

Check each character individually in a real dictionary

- meanings (primary & common ones)

- example words

- tone, commonness, any warnings (“rare character”, “archaic”)

-

Search the full name in Chinese (with characters)

- Do real people have this name? (Good sign.)

- Does it show up in novels, memes, suspense dramas about serial killers? (Maybe not so good.)

- Any big brands using it?

-

Ask at least one native speaker Very simple questions:

- “If you see this name on paper, boy, girl, or ???”

- “First impression: normal? weird? very old? very edgy?”

- “Anything awkward or funny about this?”

-

Decide context-specific rules

- For tattoo: avoid characters you don’t understand and can’t write yourself.

- For brand: avoid hard-to-type rare characters and names that collide with existing trademarks, or sound too close to them.

-

Polish with culture, not just superstition If you care about 五行 / stroke counts, fine — but treat that as last seasoning, not the main ingredient. Get the language right first. Then let traditional systems adjust among already good options.

Tattoo Reality Check: A 10-Question Checklist

Before you tattoo any Chinese name (generator-born or not), run this:

- Can you write every character by hand, from memory?

- Can you explain the meaning of each character and the whole name in your own words?

- Have two unrelated native speakers said “yeah, that’s fine / nice” without making a face?

- Did you check at least one good dictionary for the main meanings and common words of each character?

- Did you check that the combo doesn’t match a famous villain, meme, or porn brand?

- Are all characters either simplified or traditional, not a random mix?

- Are the tones and pronunciation clear enough that you can introduce yourself with this name without stumbling?

- Is the style appropriate for your age and context (not grandma, not 13-year-old edgelord, unless that’s intentional)?

- If someone asks ‘Why this name?’, do you have a story better than “a website spat it out”?

- If a Chinese friend gently told you “this is really weird”, would you be willing to change it before the tattoo, or are you more attached to the font preview than to the meaning?

If you can’t honestly answer “yes” to at least 7–8 of these, you are not ready to put this name on your body.

What a Good Chinese Name Workflow Looks Like

Just to be fair, here’s what a healthy process looks like — with or without a generator.

-

Start from purpose & identity

- pen name vs legal name vs social handle vs tattoo

- masculine / feminine / neutral

- grounded / poetic / playful / corporate

-

Choose a simple, natural surname (or decide you genuinely only need a given name / nickname).

-

Collect candidate characters that match your personality and values:

- nature: 林 (forest), 星 (star), 雨 (rain), 岚 (mountain mist)

- virtues: 诚 (honest), 安 (peace), 勇 (brave), 智 (wise)

- art/intellect: 文 (literature), 墨 (ink), 书 (book), 思 (thought)

-

Ask for help designing combinations, from:

- a knowledgeable friend,

- a tutor,

- or a tool that actually explains why it chose those characters.

-

Check them culturally

- gender feel, generation feel, region feel

- Google/Baidu/name-search sanity check

- usage in real life, not just in anime

-

Live with your finalists for a week

- write them by hand,

- use them in mock signatures or social usernames,

- see which one feels natural over time.

-

Only after all that should you think about tattoos, logos, official documents.

Generators can fit into step 3 (character ideas) or 4 (rough proposals), but they should never be step 7.

So… Are All Chinese Name Generators Trash?

Not necessarily.

There are better tools that:

- explain pinyin, tones, and meanings clearly

- flag rare or archaic characters

- let you choose style (classic, modern, gender-neutral)

- nudge you toward realistic surname–given name structures

- encourage native-speaker review instead of promising “perfect name in one click”

The real danger isn’t the code; it’s the expectation:

“I clicked a button so I must now own a deep, authentic Chinese identity.”

You don’t.

You own a suggestion.

A good generator knows that and tries to guide you into a conversation with the language, with real people, and with yourself.

A bad one… just wants you to screenshot the result and go to the tattoo shop.

Final Thought

Chinese characters are beautiful and heavy: each one carries history, culture, and daily usage patterns that tools can’t fully see.

If you’re about to put them on your skin — or on a brand you care about — they deserve more than a random mashup.

Use generators as sparring partners, not gods. Talk to real humans. Check meanings. Slow down.

The characters will still be beautiful tomorrow. Your tattoo artist can wait an extra week.

Related Articles

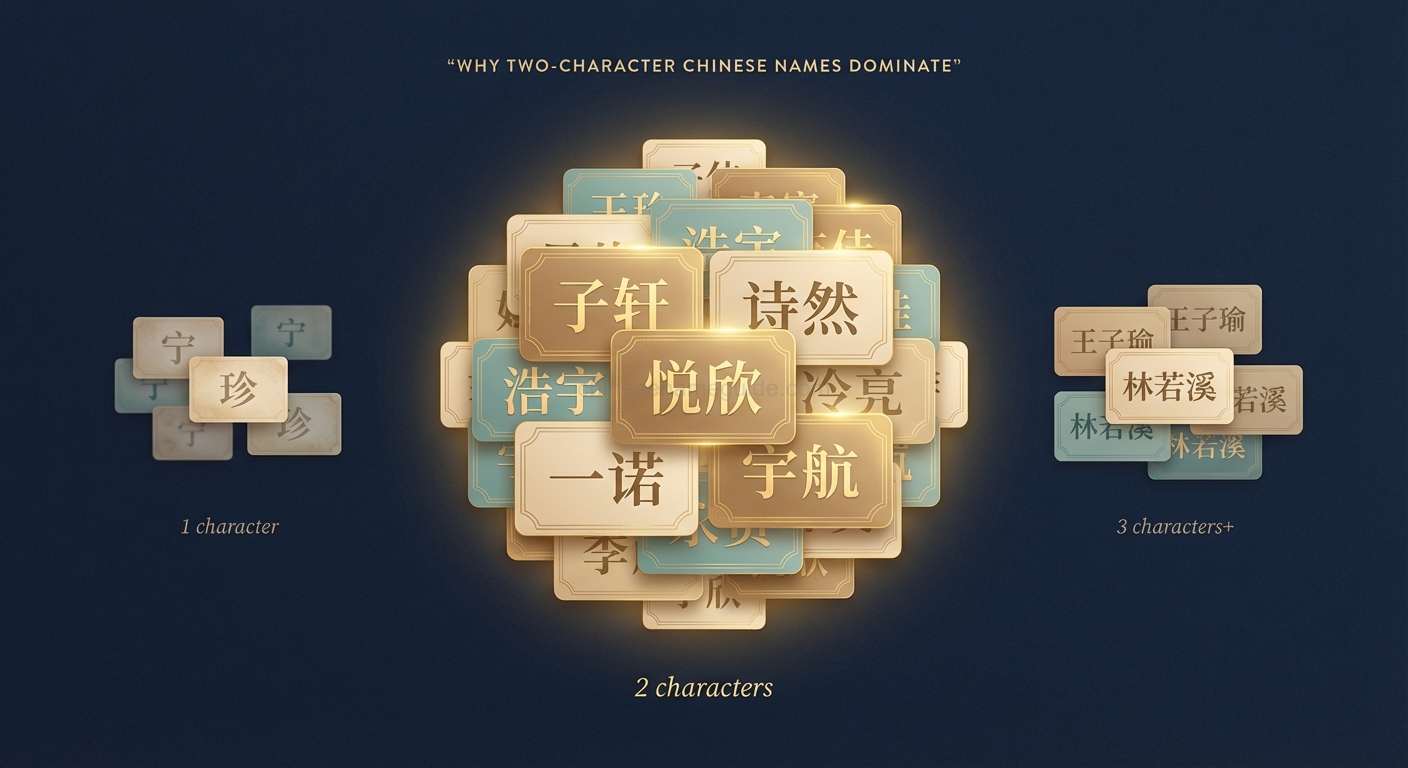

Modern Chinese Names: What Kids Are Actually Called Now

Forget Li Ming and Wang Wei. A ground-level look at what Chinese kids are really named today, what those names signal, and how to sound modern without sounding ridiculous.

When Your Chinese Name Is Just Your English Name in Characters

An in-depth look at Chinese names that are pure transliterations of English names—how they’re built, how native speakers perceive them, and when they’re useful or risky.