A Friendly, Systematic Guide to Chinese Pronunciation for Beginners

A clear and systematic guide to mastering Chinese pronunciation, covering pinyin, tones, difficult sounds, and practical tips for improvement.

If you’re learning Chinese (Mandarin), the very first wall you’ll hit is pronunciation.

The sounds look familiar because of pinyin (the Roman letters), but they don’t match English. On top of that, every syllable has a tone. One small change in pitch can completely change the meaning.

This guide walks you through Chinese pronunciation in a clear, systematic way:

- What “pronunciation” means in Mandarin

- The pinyin system: initials, finals, syllables

- Tones and why they matter

- The most common difficult sounds for English speakers

- Tone change rules you actually need

- Rhythm, sentence melody and name pronunciation

- Practical tips to improve quickly

Big Picture: How Mandarin Pronunciation Works

Before diving into details, it helps to know what you’re dealing with.

-

Mandarin is syllable-based.

Every word is made of one or more syllables. Each syllable:- has a sound (like ma, liang, zhong)

- carries a tone (pitch pattern)

-

Each syllable maps to a character.

In writing, each syllable corresponds to one Chinese character (汉字, hànzì). For example:- mā → 妈 “mother”

- mǎ → 马 “horse”

-

Pinyin is a pronunciation guide, not the language itself.

- Pinyin uses the Latin alphabet to represent sounds.

- It looks like English spelling, but the pronunciation rules are different.

To pronounce Chinese well, you need to understand:

- the building blocks of syllables (initials + finals)

- the tones

- a few sound patterns that don’t exist in your native language.

Pinyin Basics: Initials, Finals, Syllables

Every Mandarin syllable (in pinyin) can be broken down into:

Initial + Final + Tone

Example: mā = m (initial) + a (final) + first tone.

1 Initials (Consonant-like sounds)

Initials are the sounds at the beginning of a syllable. Some are close to English; others are quite different.

Close to English:

- b, p, m, f as in ba, pa, ma, fa

- d, t, n, l as in da, ta, na, la

- g, k, h as in ga, ka, ha (h is a bit harsher, like in “Bach”)

Dental sounds:

- z, c, s:

- z ≈ “ds” in “kids” → zi

- c ≈ “ts” in “cats” → ci

- s as in “see” → si

Retroflex (tongue curled slightly back):

- zh, ch, sh, r:

- zh somewhat like “j” in “job” but retroflex → zhi

- ch like “ch” in “church” but retroflex → chi

- sh like “sh” in “shoe” but retroflex → shi

- r similar to English “r” in “right”, but with a friction/“zh” feel → ri

Palatal sounds (tongue high, close to hard palate):

- j, q, x:

- j like “jee” but with lips unrounded → ji

- q like a sharp “chee” → qi

- x like a soft “sh” = German “ich”, English “she” but mouth more spread → xi

Tip: Feel the position of your tongue and lips. Mandarin consonants are very “clean”, with controlled aspiration in pairs like b/p, d/t, g/k.

2 Finals (Vowel + optional ending)

Finals are the part after the initial: -a, -ai, -ang, -ong, etc.

Some important finals:

Simple vowels:

- a as in “father” → ba

- o like “or” but shorter → bo

- e (pinyin “e”) is a very Chinese sound, between English “uh” and “er” → he, de

- i like “ee” in “see” → li

- u like “oo” in “food” → tu

The ü vowel:

- ü (written as ü, yu, ju, qu, xu)

- Shape lips like “oo”, but tongue in position for “ee”.

- Example: lǜ 绿 “green”

Nasal endings:

- -n: an, en, in, un

- -ng: ang, eng, ing, ong

For most learners, -n is “n” in “no”, -ng is “ng” in “song”.

Common issue: mixing up -n and -ng can change words:

- wán (玩, “to play”) vs wǎng (往, “towards”)

3 “Null initial” and y/w spellings

Sometimes there is no consonant initial. The syllable starts directly with a vowel. In pinyin, this is often written with a “y” or “w”:

- ya = [j] + a (written “y” but actually a glide)

- wo = [w] + o

- yi, yu, yin, yong, etc.

Phonetically, there is always something at the start: a consonant or a glide.

Tones: The Heart of Mandarin Pronunciation

Mandarin is a tonal language. This means:

Changing the pitch pattern (tone) on a syllable changes the meaning.

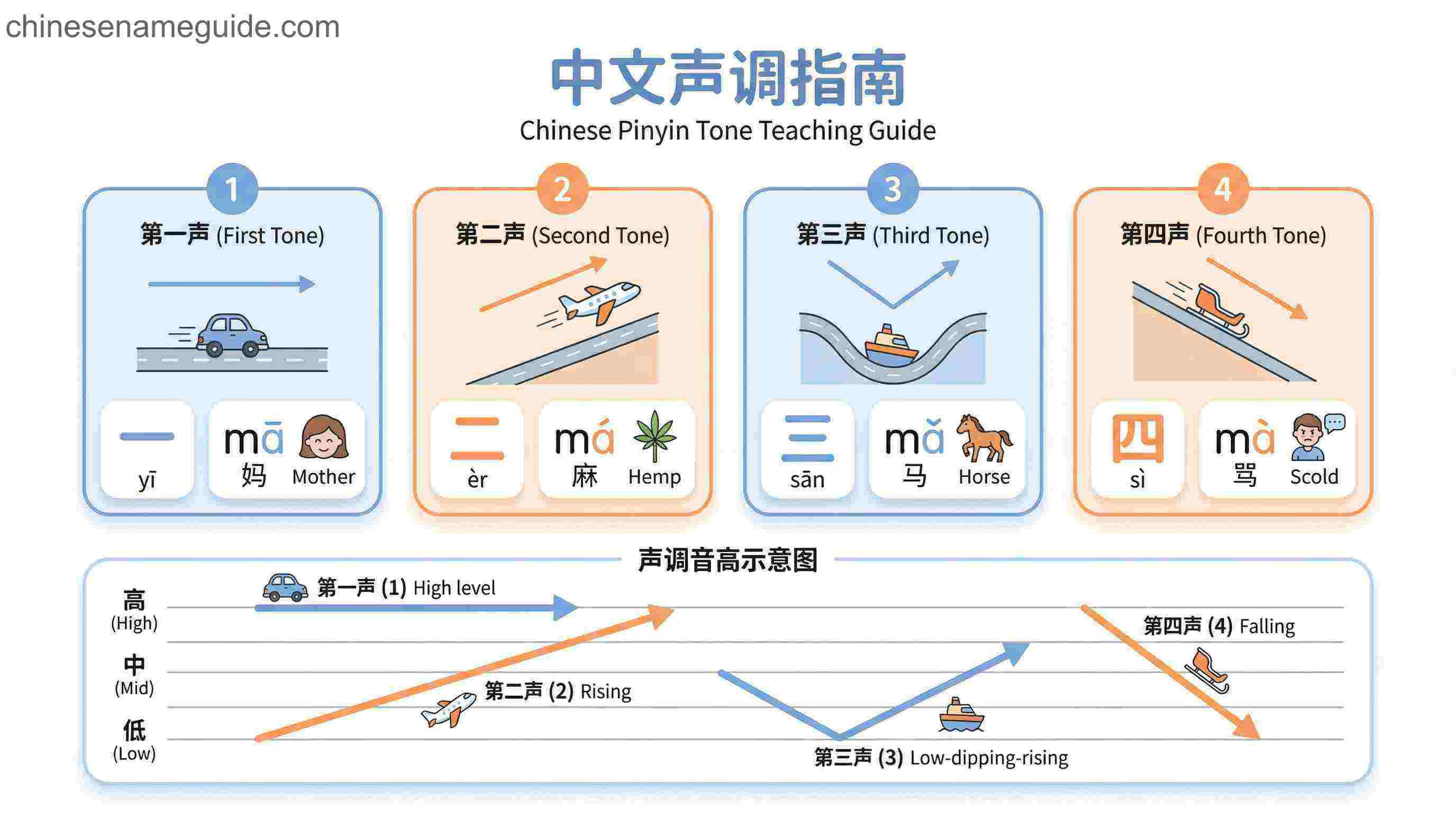

1 The four tones + neutral tone

Using the syllable ma as an example:

-

First tone (mā) – high and level

- Example: 妈 (mā, “mother”)

- Think of holding a musical note: “ma——”

-

Second tone (má) – rising, like asking a question

- Example: 麻 (má, “hemp”)

- Imagine you say “ma?” with a questioning tone.

-

Third tone (mǎ) – low dipping (fall then rise)

- Example: 马 (mǎ, “horse”)

- In careful speech it goes down then up; in fast speech it often just sounds low.

-

Fourth tone (mà) – sharp falling, like a short exclamation

- Example: 骂 (mà, “to scold”)

- Imagine saying “HEY!” or “NO!” with a strong downward pitch.

-

Neutral tone (ma) – light and short

- Example: 吗 (question particle)

- Very quick and weak; pitch depends on the previous syllable.

2 Why tones matter

Without tones, many words collapse into the same sound.

- mā, má, mǎ, mà are all different characters and meanings.

- shì could mean “to be” (是), “thing” (事), “city” (市), “world” (世) depending on tone and context in compound words.

Tones are not “extra decoration”. They are part of the word, like vowels and consonants.

Common Pronunciation Traps

If your native language is English or another non-tonal language, here are the usual trouble spots.

1 zh / ch / sh / r vs z / c / s

Two series of sounds are easy to confuse:

- z, c, s (front of the mouth, tongue near teeth)

- zh, ch, sh, r (tongue curled slightly back, retroflex)

Examples:

- zài (在, “at”) vs zhài (寨, “village/stockade”)

- sān (三, “three”) vs shān (山, “mountain”)

- cài (菜, “vegetable”) vs chài (柴, “firewood”)

Practice tip: Say English “sir” and then curl your tongue a bit more back — you’re close to sh / zh.

2 j / q / x

These look like English letters but sound different:

- j: like “jee” but tongue against the hard palate, lips unrounded → jī

- q: a strong version of j + “ch” type release → qī (“chee” with spread lips)

- x: like a soft “sh”, similar to German “ich” → xī

Compare:

- jī 鸡 “chicken”

- qī 七 “seven”

- xī 西 “west”

3 ü vs u

- u: like “oo” in “food” → lù 路 “road”

- ü: tongue high and front (like “ee”) but lips rounded → lǜ 绿 “green”

In pinyin:

- ü becomes u after j, q, x, y (because no regular u can follow them):

- ju, qu, xu, yu are actually jü, qü, xü, yü

So qu is not “koo”, it’s “chyü”.

4 -n vs -ng

Many learners soften everything into -n or -ng, but Mandarin keeps them distinct.

- -n: tip of the tongue touches upper teeth ridge → ān, èn, yín

- -ng: back of the tongue raises to the soft palate → áng, ēng, yīng, yǒng

Minimal contrasts:

- wán (玩, “to play”) vs wǎng (往, “towards”)

- lín (林, “forest”) vs lǐng (领, “collar/lead”)

Essential Tone Change Rules (Tone Sandhi)

In real speech, tones are not always pronounced exactly as in the dictionary. Some automatic changes happen. The good news: there are only a few rules you really need.

1 Third tone + third tone → 2nd + 3rd

When two third tones come together:

3rd + 3rd → 2nd + 3rd

Examples:

-

你好 (nǐ hǎo in dictionary)

- Actually pronounced: ní hǎo (2nd tone + 3rd tone)

-

很好 (hěn hǎo, “very good”)

- Pronounced: hén hǎo

You don’t change the written tone mark; it’s just how you say it.

2 不 (bù, “not”) tone change

Before another fourth tone, bù changes from 4th tone to 2nd tone:

- 不 + 是 (bù shì) → bú shì (“is not”)

- 不 + 对 (bù duì) → bú duì (“not correct”)

3 一 (yī, “one”) tone change

- When counting alone, it’s first tone: yī.

- Before a fourth tone, it becomes second tone:

- 一 + 见 (yī jiàn) → yí jiàn

- Before a first, second, or third tone, it becomes fourth tone:

- 一 + 天 (yī tiān) → yì tiān

Don’t panic about these at the start; focus on recognizing the pattern and gradually using it.

Rhythm, Sentence Melody, and Chinese Names

1 Syllable-timed rhythm

Mandarin is often described as more syllable-timed than English. That means:

- each syllable tends to take a similar amount of time

- you don’t stretch certain syllables as much as in English words

Compare:

- English “computer” → comPUter (stress in the middle)

- Chinese diànnǎo (电脑) → diàn + nǎo (two clear, similar-length syllables)

2 Neutral tone and “weak” syllables

Many particles and some second syllables in words are pronounced with a neutral tone:

- māma 妈妈 (mother) → mā + ma (second syllable light and short)

- shénme 什么 (what) → shén + me (light me)

This creates a natural rhythm: strong + weak, strong + weak.

3 Pronouncing Chinese names

Most Chinese given names have two syllables, and surnames are usually one syllable (with some two-syllable exceptions).

Typical structure:

Surname (1 syllable) + Given name (1 or 2 syllables)

Examples in pinyin:

- Zhāng Wěi 张伟

- Lǐ Nà 李娜

- Wáng Jiāmíng 王家明

Pronunciation tips:

-

Say each syllable clearly with its tone.

- Zhāng (first tone) + Wěi (third tone)

- Don’t flatten tones; “Zhang Wei” with English intonation can sound like a different name.

-

Don’t shift stress like in English.

- It’s not “ZHANG wei” or “zhang WEI”; both syllables get attention, shaped by tones.

-

Watch consonants.

- Zhāng starts with zh, not English “j” or “z”.

- Wěi uses the w + ei final, like “way” but with the correct tone.

Practical Strategies to Improve Your Pronunciation

You don’t need “perfect” pronunciation to communicate, but getting closer will help—from daily conversations to saying people’s names correctly.

1 Train your ear first

- Use minimal pairs (ma1 / ma2 / ma3 / ma4) and listen repeatedly.

- Try to identify tones and sounds before you try to produce them.

- Use audio from native speakers (podcasts, short videos, courses).

2 Shadow native audio

- Pick a short clip of a native speaker (10–20 seconds).

- Listen once without speaking.

- Then play it again and repeat immediately after, copying:

- consonants & vowels

- pitch (tone) patterns

- rhythm and speed

Do this daily—your mouth will gradually learn the correct “shape”.

3 Isolate tricky sounds

Choose one problem at a time:

- Day 1–2: only practice zh/ch/sh/r vs z/c/s

- Day 3–4: only practice j/q/x

- Day 5–6: only practice ü and -n/-ng

Make your own word lists and drill them for 5–10 minutes per day.

4 Visualize tones

Many learners find it helpful to draw the tone:

- first tone → a flat horizontal line

- second tone → a rising diagonal line

- third tone → a dip “∨”

- fourth tone → a downward diagonal “”

When you say a word, imagine your voice drawing that line.

5 Ask for feedback (and really listen)

When talking to native speakers:

- ask “Is my tone okay?” for specific words

- invite them to repeat your incorrect pronunciation so you can compare

- don’t be shy about repeating after them several times

Conclusion: Focus on Foundations, Not Perfection

Chinese pronunciation looks intimidating, but it’s a finite system:

- a limited set of initials and finals

- four main tones (plus neutral)

- a few predictable tone change rules

If you get:

- basic pinyin sounds right, and

- tones roughly correct,

you’ll already be far ahead of many learners who skip this foundation.

Start small:

- Learn initials and finals.

- Get comfortable with all four tones on simple syllables.

- Practice with real words and especially people’s names.

Bit by bit, your mouth and ears will adjust. Chinese will start to sound less like noise and more like patterns you can recognize, imitate, and finally use with confidence.

Related Articles

How to Pronounce Chinese Names with Pinyin: A Practical Guide for Non-Native Speakers

A practical guide to pronouncing Chinese names written in pinyin, covering name structure, pinyin basics, common patterns, and practice tips for non-native speakers.

Common Tone Mistakes and How to Finally Fix Them

A deep, practical guide to the most common Mandarin tone mistakes learners make — with clear examples, explanations, and training strategies to fix them for good.