Common Tone Mistakes and How to Finally Fix Them

A deep, practical guide to the most common Mandarin tone mistakes learners make — with clear examples, explanations, and training strategies to fix them for good.

If you’ve studied Mandarin for a while, you’ve probably felt this:

“I know the tones, but when I speak… they disappear.”

You memorize mā / má / mǎ / mà, but in real words and sentences everything collapses into “ma??” Native speakers guess from context, and you walk away thinking:

- “Maybe tones are not that important?”

- “Maybe I’m just tone-deaf?”

The bad news: tones never stop mattering.

The good news: most problems come from a few very predictable mistakes — and they are fixable.

This article goes deep into common Mandarin tone mistakes, why they happen, and concrete ways to fix them:

- Treating tones like optional decorations

- Misunderstanding what the 3rd tone really is

- Ignoring tone changes (tone sandhi)

- Using “dictionary tones” instead of “sentence tones”

- Confusing tones with sentence intonation

- Over-pronouncing or under-pronouncing the neutral tone

- Memorizing tones for single syllables, not words

- Letting English (or your L1) rhythm override your tones

- Having no feedback loop (you never hear your own tones)

Treating Tones Like Optional Decorations

Mistake:

You treat tones as “nice to have”, not part of the syllable. You focus on consonants and vowels, and maybe add a tone if you remember.

What this looks like:

- You say ma in four different contexts, with vague pitch.

- Your Pinyin notes have many syllables with no tone marks.

- When you learn new words, you remember “shénme means ‘what’” but not that it’s shénme (2 + neutral).

Why this is a problem

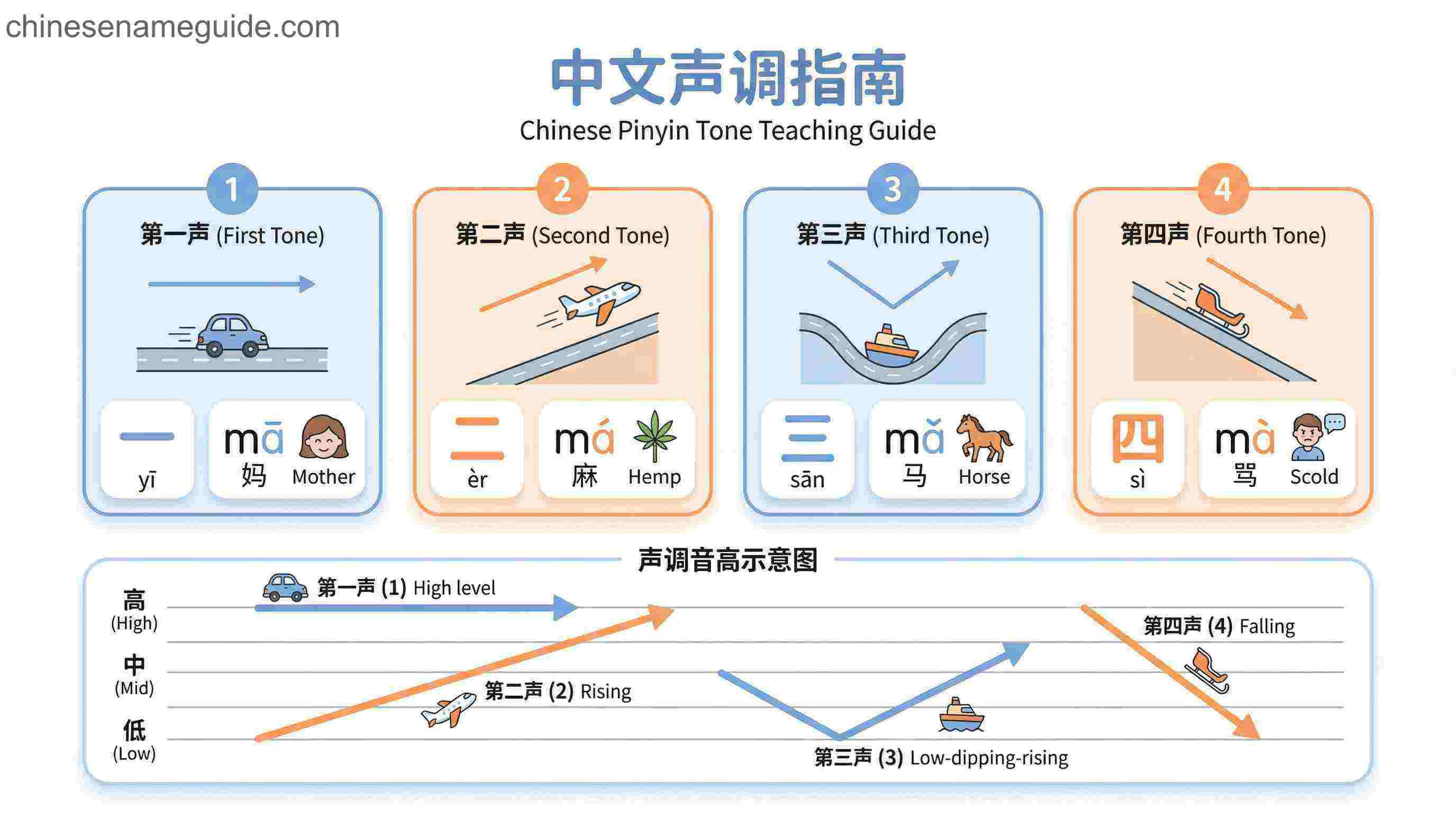

In Mandarin, tone is part of the word, not extra “emotion” on top:

- 妈 mā (1st) – mother

- 麻 má (2nd) – hemp

- 马 mǎ (3rd) – horse

- 骂 mà (4th) – to scold

If you ignore tones, you’re basically spelling words wrong every time you open your mouth.

How to fix it

-

Change your mental model:

Every Chinese syllable has initial + final + tone. Missing the tone feels as wrong as missing the vowel. -

Always write tone marks in your notes.

No Pinyin without tones. If you don’t know the tone, leave a question mark and fix it later (ma?), but don’t leave it blank. -

Learn vocab as “sound bundles”, not English equivalents.

Instead of:“谢谢 = thank you”

Train: xièxie (4 + neutral) = 谢谢 = thank you

Misunderstanding the 3rd Tone (The “Low” Tone vs the “Dip”)

Mistake:

You learn that the 3rd tone “dips down then goes up”, so you pronounce every 3rd tone like a dramatic dip ⤵︎⤴︎ — even in the middle of sentences.

What this looks like:

- You say hěn hǎo as two big roller coasters: hěěěn (down then up) + hǎǎǎo.

- Sentences become very slow and wavy because you’re trying to draw the full 3rd tone contour each time.

Reality:

In natural speech, the 3rd tone is usually a low, half-dipped tone, and it only fully “dips then rises” when:

- it’s alone, or

- it’s at the end of a phrase and clearly emphasized.

In combinations:

- 很好 hěn hǎo is more like hen2 hao3 (see tone sandhi below)

- 你好 nǐ hǎo is actually ní hǎo in real speech (first syllable rises)

How to fix it

-

Think “low tone”, not “roller coaster tone”.

For 3rd tone inside sentences, aim for a low pitch that may slightly dip, but doesn’t waste time going up again. -

Practice minimal pairs with audio:

- 2nd vs 3rd:

- 麻 má (2nd) – hemp

- 马 mǎ (3rd) – horse

Focus on: 2nd tone rises, 3rd tone stays low.

- 2nd vs 3rd:

-

Record yourself saying sequences like:

- 很好、很好、很好 (hěn hǎo)

- 我很忙 (wǒ hěn máng)

Then compare with native recordings. Your 3rd tones should be shorter and lower than what textbooks draw.

Ignoring Tone Changes (Tone Sandhi)

Mistake:

You learn tones character-by-character, but when those characters join into words or phrases, you always pronounce the original dictionary tones, ignoring tone sandhi (tone change rules).

Big ones you must know:

1 3rd + 3rd → 2nd + 3rd

When you have two 3rd tones in a row, the first becomes a 2nd tone:

- 你好 nǐ hǎo → ní hǎo

- 很好 hěn hǎo → hén hǎo (often written hěn hǎo, but pronounced with rising first syllable)

- 也许 yě xǔ → yé xǔ

In longer chains of 3rd tones, patterns get more complex, but for beginners and intermediates:

Start by fixing 2-syllable 3rd + 3rd combinations first.

2 不 bù and 一 yī tone changes

-

不 normally is bù (4th), but before another 4th tone it becomes bú (2nd):

- 不对 bù duì → bú duì (not correct)

- 不会 bù huì → bú huì (won’t / can’t)

-

一 normally is yī (1st), but:

- before 4th tone → yí + 2nd:

- 一样 yī yàng → yí yàng (the same)

- 一定 yī dìng → yí dìng

- before 1st/2nd/3rd tone → yì + 4th in many cases:

- 一个 yī gè → yí gè (colloquial)

- 一般 yī bān → yì bān

- before 4th tone → yí + 2nd:

How to fix it

-

Make a tone change list in your notes:

- 3–3 pairs you use often (你好、很好、挺好、可以、也许…)

- Common 不 + verb phrases

- Common 一 + measure word patterns

-

Practice them as fixed chunks with correct tones, not as separate characters.

-

When reading aloud, underline words that trigger sandhi and consciously change them.

Using “Dictionary Tones” Instead of “Sentence Tones”

Mistake:

You pronounce each syllable with its full dictionary tone, very slowly and separately:

Wǒ (3rd) | shì (4th) | Měiguó (3rd + 2nd) | rén (2nd).

It sounds like you’re reading a tone chart, not speaking.

Why this happens

- Textbooks teach tones in isolation, and learners never train the flow of tones in real sentences.

- People are afraid of “losing” the tones, so they over-articulate every one.

What native speech does

- Tones keep their identity, but their shape is slightly compressed and smoothed inside longer sentences.

- Tone + rhythm interact; unstressed syllables may be less prominent, but still tonal.

How to fix it

-

Practice short, natural sentences at normal speed, not just single words. For example:

- 我很好。Wǒ hěn hǎo.

- 你去哪里?Nǐ qù nǎlǐ?

- 这本书很好看。Zhè běn shū hěn hǎokàn.

-

Use shadowing:

- Find a slow native recording (podcast, graded reader, YouTube, etc.).

- Play one short sentence.

- Repeat immediately, mimicking the musical line (pitch + rhythm), not just the segmental sounds.

-

Accept that natural tone shapes are a bit simpler than textbook tone diagrams. Focus on being clearly distinguishable, not theatrically “perfect”.

Confusing Tones with Sentence Intonation

Mistake:

You use big English-style rising intonation for questions and falling intonation for statements, and that intonation overrides your tones.

Example:

- You say “你好吗?” with a huge rise at the end like English “You oKÁY?” → your mǎ suddenly sounds like má or ma?.

Important idea:

In Mandarin, tone and intonation are layered, not one replacing the other.

- Tone is local: it belongs to each syllable.

- Intonation (question, surprise, emphasis) is more global: it slightly adjusts the whole pitch range, but should not change which tone each syllable is.

How to fix it

-

Practice yes/no questions with the 吗 (ma) neutral tone:

- 你好吗?Nǐ hǎo ma?

- 你是老师吗?Nǐ shì lǎoshī ma?

Keep 吗 light and short; don’t give it a big rising tone.

-

Practice question words (who, what, where):

- 你去哪里?Nǐ qù nǎlǐ?

- 你喜欢什么?Nǐ xǐhuan shénme?

Notice: the question word carries its own tone; you do not need an extra giant rise at the end.

-

Record both statements and questions:

- 你去北京。Nǐ qù Běijīng.

- 你去北京吗?Nǐ qù Běijīng ma?

Compare pitch: the question can rise a bit globally, but each syllable’s tone type should remain recognizable.

Neutral Tone: Over-Pronounced or Ignored

Mistake A – You over-pronounce the written tone of particles.

You say:

- de (的) as full dí / dì,

- ma (吗) as full má / mǎ / mà,

- le (了) as full lé / lè.

Result: everything sounds overly heavy, and your speech rhythm is weird.

Mistake B – You flatten everything to neutral, losing contrast.

You say many content words with almost no tone, relying on context. This can confuse listeners, especially outside very simple phrases.

What neutral tone really is

Neutral tone is:

- shorter and lighter than full tones,

- pitch is determined by the preceding tone,

- used in many grammatical particles and the second syllable of common words:

Examples:

- 谢谢 xièxie – 4 + neutral

- 妈妈 māma – 1 + neutral

- 多少 duōshao – 1 + neutral (very common in Mainland speech)

- 什么 shénme – 2 + neutral

How to fix it

-

Mark neutral tone in your notes as “·” or with no tone mark, but explicitly note it:

- māma (妈·妈)

- xièxie (谢·谢)

- shénme (什·么)

-

Practice contrast drills:

- 妈 mā (1st, stressed) vs 妈妈 māma (1st + neutral)

- 要 yào (main verb “to want”) vs 要是 yàoshi (“if”, first syllable stressed, second lighter)

-

Learn some “neutral tone phrases” as chunks:

- 对不起 duìbuqǐ – 4 + neutral + 3

- 知道了 zhīdào le – 1 + 4 + neutral

Say them at natural speed; feel how the neutral syllable shrinks.

Memorizing Tones for Characters, Not Words

Mistake:

You know each character’s tone, but you don’t know the tone pattern of the whole word. So you:

- say 生 as shēng or shéng or shèng randomly in different words

- forget that words like 先生 are xiānsheng (1 + neutral), not two full tones

Why this matters

Mandarin is lexicalized: many characters have multiple readings (tones) depending on the word:

- 行 – xíng (“OK, go, capable”), háng (“line, trade”)

- 好 – hǎo (good), hào (to like, as in 爱好 àihào)

- 长 / 長 – cháng (long), zhǎng (to grow, boss)

If you only memorise “好 is 3rd tone”, you’ll mispronounce:

- 爱好 àihào (4 + 4) – hobby

- 好像 hǎoxiàng (3 + 4) – it seems

- 好的 hǎode (3 + neutral) – OK

How to fix it

-

Always learn words, not isolated characters:

- 好 → hǎo = good (adj), but

- 爱好 àihào = hobby (verb/object),

- 好像 hǎoxiàng = it seems.

-

In your vocab list, write word-level tone patterns:

- 先生 xiānsheng (1 + ·)

- 中国 Zhōngguó (1 + 2)

- 学生 xuésheng (2 + ·)

-

Use color-coding or underlines for tricky cases:

- 行:xíng ✅ / háng ✅ → always store with example words.

Letting Your Native Language Rhythm Override Tones

Mistake:

You bring your native language’s stress-timed rhythm into Mandarin:

- You heavily stress every few syllables and squash others, regardless of their tones.

- You place stress based on the English translation, not the Chinese word.

Result: even if you “know” the tones individually, the global stress pattern distorts them.

Examples:

In English:

“I DON’T really KNOW.”

You might say in Chinese:

我 不太 知道。Wǒ bú tài zhīdào.

But if you import the English stress, you may:

- over-emphasize 不 and 知,

- flatten the rest, making tài indistinct.

How to fix it

-

Listen carefully to native sentences and mark which syllables are slightly more prominent. Often Chinese stress is:

- on content words,

- but more evenly distributed than English.

-

Practice slow, evenly-timed speech at first:

- 我 / 不 / 太 / 知 / 道

keeping each syllable clear and tonal.

- 我 / 不 / 太 / 知 / 道

-

As you speed up, keep the tonal contrast even when some syllables are less loud.

-

Use clap or tapping exercises:

- Tap once per syllable as you say a sentence; avoid long gaps or “swallowed” syllables.

No Feedback Loop: You Never Hear Your Own Tones

Mistake:

You practice a lot, but:

- you never record yourself,

- you don’t compare with natives,

- you rarely get targeted correction on tones.

Without feedback, your mouth keeps reinforcing whatever pattern feels easy, not what’s correct.

How to fix it (simple feedback routine)

Pick a short text (2–4 sentences) and do this weekly:

-

Listen to native audio

- From a graded reader, textbook audio, podcast snippet, etc.

- Listen several times, focusing on melody (tone flow + rhythm).

-

Record yourself reading the same text

- Use your phone; no special equipment needed.

- Do one version slowly and one at natural speed.

-

A–B comparison

- Play the native audio for one sentence.

- Immediately play your version of the same sentence.

- Note where your pitch pattern diverges obviously.

-

Micro-drill problem spots

- If you notice 3–3 combinations or bu/yi pronounced wrong → isolate and drill those phrases.

- If neutral tones are too heavy → re-record with shorter, lighter neutral syllables.

-

Optional: ask a native friend/teacher

- “Please circle any words where my tone is wrong or sounds strange.”

- Fix those before learning another 500 new words.

Putting It All Together

Most Mandarin tone problems come down to a few recurring patterns:

- you don’t treat tones as part of the word,

- you over-dip the 3rd tone,

- you ignore common tone changes,

- you speak in “dictionary mode”, not sentence mode,

- your English (or other L1) intonation fights your tones,

- you haven’t built a habit of hearing and correcting yourself.

The solution isn’t magic or talent; it’s:

-

Change your mental model:

Every syllable = initial + final + tone, no exceptions. -

Master a few core rules:

- 3rd + 3rd → 2nd + 3rd

- 不 and 一 tone changes

- neutral tone behavior in common words

-

Practice tones in context:

Short phrases & real sentences > isolated syllables. -

Create a feedback loop:

Record → compare → correct → repeat.

Related Articles

How to Pronounce Chinese Names with Pinyin: A Practical Guide for Non-Native Speakers

A practical guide to pronouncing Chinese names written in pinyin, covering name structure, pinyin basics, common patterns, and practice tips for non-native speakers.

A Friendly, Systematic Guide to Chinese Pronunciation for Beginners

A clear and systematic guide to mastering Chinese pronunciation, covering pinyin, tones, difficult sounds, and practical tips for improvement.