Learn How Chinese Surnames Work: Structure, Meaning, and Real-Life Use

A clear, practical guide to how Chinese surnames work – from Wang and Li to rare double surnames, naming order, marriage, and how foreigners should use them correctly.

If you’ve met people called Li Wei, Wang Jing, or Chen Yu, you’ve already seen one big difference between Chinese and Western names:

The surname comes first.

But once you look deeper, Chinese surnames are full of patterns and surprises:

- a tiny set of surnames covers most of the population

- almost all surnames are one character long

- a few are double surnames like 欧阳 (Ōuyáng) or 司马 (Sīmǎ)

- women usually do not change their surname after marriage

- the same surname can look totally different in English: Chen / Chan / Tan – and they’re all 陈

This guide is a practical walkthrough of how Chinese surnames work:

- Basic structure of Chinese names

- How common the big surnames really are

- The classic “Hundred Family Surnames” text

- Single-character vs. compound (double) surnames

- How surnames are inherited and used today

- How the same surname shows up as Li / Lee / Lai etc. in English

- Tips for foreigners: reading, using, and choosing a Chinese surname

The Basic Structure: Surname First, Then Given Name

In modern Standard Chinese (Mandarin), a full name is usually:

[Surname] + [Given name (1–2 characters)]

Examples:

- 李雷 (Lǐ Léi) – surname 李, given name 雷

- 王小明 (Wáng Xiǎomíng) – surname 王, given name 小明

- 陈静 (Chén Jìng) – surname 陈, given name 静

Key points:

- The surname almost always has one syllable and one character.

- The given name has one or two characters (two is more common today).

- When written in English contexts, many people keep Chinese order (Wang Xiaoming), but some flip to Western order (Xiaoming Wang). Context usually tells you which is which.

Official documents in Chinese (ID, hukou, etc.) always use the Chinese order: surname first.

How Common Are the Big Surnames?

Chinese surnames are extremely concentrated:

- The top 100 surnames (all one-syllable) cover about 85% of people in mainland China.

- A handful like 王 Wáng, 李 Lǐ, 张 Zhāng, 刘 Liú, 陈 Chén are each used by tens of millions of people.

Different sources give slightly different rankings, but they all agree on a stable “big club” at the top. For example, recent lists of common surnames usually start like this:

- 李 Lǐ

- 王 Wáng

- 张 Zhāng

- 刘 Liú

- 陈 Chén

- 杨 Yáng

- 赵 Zhào

- 黄 Huáng

- 周 Zhōu

- 吴 Wú

So if you randomly invent “Li Wei” as a character name, you’ve basically named them “John Smith” — perfectly realistic, but also extremely common.

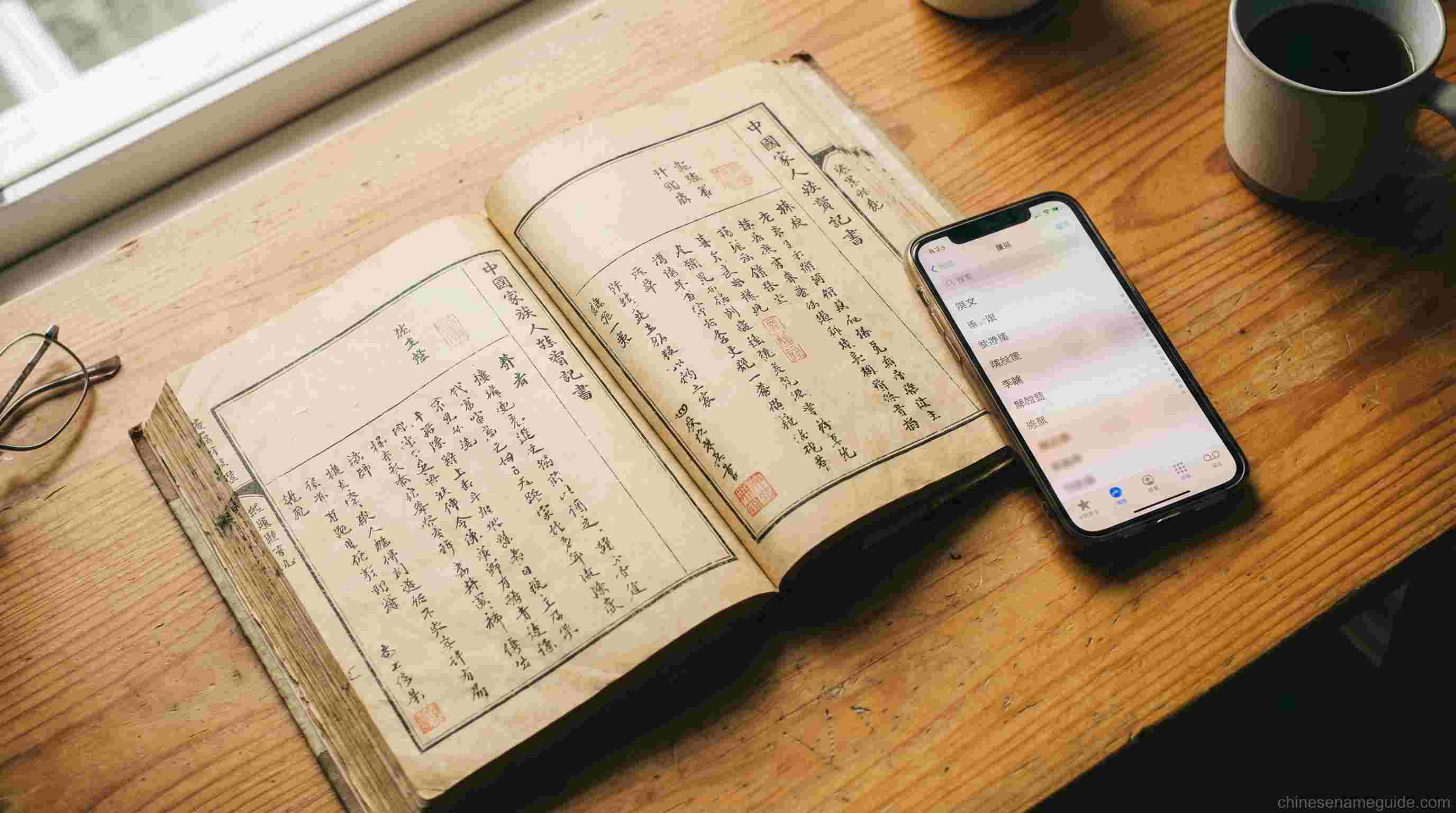

The “Hundred Family Surnames” (百家姓)

Historically, Chinese people memorized a classic called 百家姓 (Bǎijiāxìng) – “The Hundred Family Surnames”.

- It was compiled in the Northern Song dynasty (10th–11th century).

- The most common version actually contains several hundred surnames arranged in rhyming four-character lines, not just 100.

- It was used as a primer to teach children characters and basic literacy, alongside texts like the Thousand Character Classic and Three Character Classic.

- It famously starts with 赵钱孙李 (Zhào Qián Sūn Lǐ) – putting the imperial surname 赵 first, then other prominent clans.

Today, 百家姓 is more cultural than practical, but you still see it referenced in:

- children’s books

- genealogy discussions

- “surname origin” websites and TV shows

You don’t need to memorize it, but it’s useful to know that Chinese people have been thinking about surnames as a system for a long time.

Single-Character vs. Compound (Double) Surnames

1 Single-character surnames (the vast majority)

Almost all surnames you meet will be one character:

- 王 Wáng

- 李 Lǐ

- 张 Zhāng

- 陈 Chén

- 林 Lín

- 何 Hé

- 马 Mǎ

- …and so on.

All of the top 100 surnames are one character, and they dominate everyday life.

2 Compound (double) surnames

A small number of families have compound surnames – two characters treated as one surname:

- 欧阳 / 歐陽 – Ōuyáng

- 上官 – Shàngguān

- 司马 / 司馬 – Sīmǎ

- 司徒 – Sītú

- 诸葛 / 諸葛 – Zhūgě

- 夏侯 – Xiàhóu

- 皇甫 – Huángfǔ

These often come from:

- ancient noble titles, official posts, or place names

- lineages of non-Han ethnic groups that were sinicized

- combinations of two older clan names

Today, only a few compound surnames (like 欧阳, 上官, 司马, 司徒) are at all common, and even they are rare compared to Li/Wang.

How to handle them as a learner:

- Treat the **two characters as one unit (欧阳 is the surname; the given name comes after it).

- So 欧阳娜娜 (Ōuyáng Nànà) has surname 欧阳, given name 娜娜.

- Don’t split them when sorting or addressing.

How Surnames Are Inherited and Used Today

1 Inheritance: mostly paternal, with some change

Traditionally:

- Children take the father’s surname.

- The mother keeps her own surname after marriage.

This is still the default in Mainland China, but family law in China now allows children to take either the father’s or mother’s surname by agreement, and some urban couples do choose the mother’s surname for their child. (Practice varies by family and region.)

In Taiwan, Hong Kong, and overseas communities, patterns are similar: women usually keep their maiden surname legally, even if some social practices follow Western norms (e.g., being addressed as “Mrs. X” in English).

2 How people address each other

Common, polite ways of calling someone in Chinese:

- [Surname] + 先生 (xiānshēng) – Mr. [Surname]

- 王先生 – Mr. Wang

- [Surname] + 女士 (nǚshì) – Ms. [Surname]

- [Surname] + 老师 (lǎoshī) – Teacher [Surname]; also used broadly as a respectful title

- In casual speech: [Surname] + given-name initial or role among friends/colleagues.

Using only the given name with no title is usually for:

- close friends

- family

- talking about a third person in an informal context

If you’re not sure, [Surname] + title is the safest and most respectful.

Do Chinese Surnames “Mean” Something?

Yes — but the relationship between literal meaning and real-life identity is not straightforward.

Many common surnames come from:

- Ancient states or places – e.g., 赵 (Zhào), 宋 (Sòng), 秦 (Qín)

- Official titles / posts – e.g., 司马 (Sīmǎ, “Master of the Horses”)

- Occupations or ranks – 师 / 師 (shī, “master”), 史 (shǐ, “historian”)

- Totemic or symbolic animals – 马 (Mǎ, “horse”), 龙 / 龍 (Lóng, “dragon”), 熊 (Xióng, “bear”)

- Founding ancestors’ personal names or courtesy names

Over time:

- Many surnames lost their obvious connection to the original meaning.

- Today, Chinese people rarely analyze someone’s surname for “luck” or personality the way some given names are scrutinized.

So:

For surnames, meaning is mostly historical and genealogical, not a daily personality label.

That said, some surnames do carry cultural associations (e.g., famous clans, historical states), which can matter in genealogy or in historical fiction.

The Same Surname, Many English Spellings

Because Chinese has many spoken varieties and multiple romanization systems, the same character can appear in English in different ways.

Take 陈 (Mandarin Chén):

- Mainland pinyin: Chen

- Cantonese (Hong Kong, overseas): Chan

- Hokkien / Teochew (Southeast Asia): Tan

Other examples:

- 李 – Lǐ → Li, but also Lee / Lei in some families

- 黄 / 黃 – Huáng → Huang, but also Wong / Hwang / Ooi depending on dialect and migration history

- 林 – Lín → Lin / Lim / Lam in different regions

So if you see Chan and Chen, they may both be 陈 in Chinese characters, just through different dialects and history.

When you’re learning:

- Always ask for the Chinese characters, not just the English spelling.

- Use characters as the ground truth; romanization is just a convenience layer.

Surnames Beyond the Mainland: Greater China & Overseas

Mainland China

- Standard written forms follow Simplified Chinese in most contexts.

- Pinyin (Mandarin) is the default romanization for official use.

Taiwan

- Uses Traditional characters officially.

- Romanization has been mixed (Wade–Giles, Tongyong, Hanyu Pinyin) and many families have fixed English spellings that don’t match any system perfectly.

Hong Kong & Macau

- Chinese is mostly written in Traditional characters.

- English spellings reflect Cantonese pronunciations (Chan, Cheung, Wong, etc.).

Singapore, Malaysia, Southeast Asia

- Large Chinese communities with surnames spelled via Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, etc.

- That’s why you see Tan, Lim, Goh, Teo, Chua, Ng, Khoo, etc., all mapping back to common characters.

For onomastics and genealogy, this diversity makes surname study in the diaspora a fascinating puzzle.

How to Use Chinese Surnames Correctly as a Learner

1 When you see a name

- Assume first syllable / first character = surname, unless you’re told it’s a double surname.

- If in doubt, ask:

- 你的姓是什么?(Nǐ de xìng shì shénme?) – “What is your surname?”

- Don’t chop off extra characters from a compound surname like 欧阳 or 司马.

2 When you address someone

- Safe default: [Surname] + title

- 王老师, 李先生, 陈总 (Boss Chen), etc.

- Avoid using just the given name with no title, unless they invite you to or the context is clearly informal.

3 When you write someone’s name in English

- Respect their chosen spelling and order: if they write “Xiaoming Wang”, copy that.

- If you must guess, a safe pattern is:

- [Given name] [Surname] in English context, with capital letters (Xiaoming Wang).

- On forms, many Chinese people write “Wang” as “family name” and “Xiaoming” as “given name”.

Choosing a Chinese Surname as a Foreigner

If you’re picking a Chinese name for yourself, your surname is one of the first decisions.

Common options:

-

Adopt a very common Chinese surname

- e.g., 王 Wáng, 李 Lǐ, 陈 Chén, 林 Lín

- Pros: feels natural, nobody thinks it’s strange

- Cons: it’s like being “Smith” or “Johnson” — very common

-

Pick a surname that loosely matches your own

- Based on sound: e.g., “Lee” → 李 Lǐ

- Based on meaning: if your surname means “forest”, 林 Lín might fit

- Try not to overthink; choose something that’s easy to pronounce.

-

Use no Chinese surname at all (just a given name)

- Okay for online handles or casual learning

- Less suitable if you want a formal, realistic full name

Whatever you choose:

- Stick with it consistently once you’ve used it in public contexts.

- Make sure the full name (surname + given name) feels natural to a native speaker; you can always ask for feedback.

Quick FAQ

Q: Are there “rare” Chinese surnames?

Yes. While the top 100 cover most people, there are thousands of surnames in total, some with very few bearers.

Q: Can Chinese people change their surname?

It’s possible but not casual; it usually requires legal procedures and a strong reason. Historically, surnames changed through adoption, imperial orders, or migration.

Q: Do women take their husband’s surname?

In most Chinese-speaking societies, no in the legal sense — women keep their own surname on official documents. In some overseas communities, they may socially use a Western-style married name in English, but Chinese legal name usually stays the same.

Q: Are double surnames higher status?

Some compound surnames originated from nobility, but in modern life, status is more about personal achievement than the surname itself. Double surnames are more “unusual” than “noble” today.

Learning how Chinese surnames work is a huge step toward understanding Chinese names as a whole. Once you can spot the surname, the rest — given names, tones, cultural meaning — becomes much easier to navigate.

Related Articles

Modern Chinese Names: What Kids Are Actually Called Now

Forget Li Ming and Wang Wei. A ground-level look at what Chinese kids are really named today, what those names signal, and how to sound modern without sounding ridiculous.

Why Most Chinese Name Generators Are Dangerous (Don't Get a Tattoo Yet!)

Before you tattoo a ‘cool Chinese name’ or launch a brand with it, read this. A brutally honest look at how most Chinese name generators actually work — and why they can quietly ruin your skin, your brand, or your reputation.